A Swashbuckling Friend of Freedom

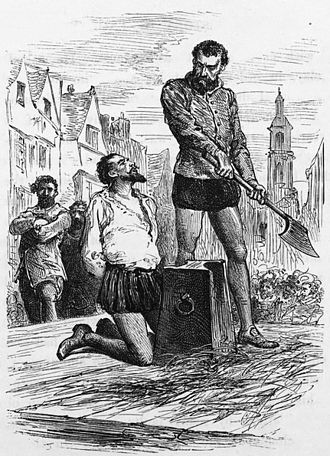

On October 29 back in 1618 Sir Walter Raleigh was beheaded on largely trumped-up charges (as noted in this series this Oct. 10). I’ve never been quite sure what to make of Raleigh.

On October 29 back in 1618 Sir Walter Raleigh was beheaded on largely trumped-up charges (as noted in this series this Oct. 10). I’ve never been quite sure what to make of Raleigh.

He is larger than life in a very Renaissance kind of way, a writer, adventurer and courtier who I expect was also more annoying than life and not just for the daunting example he set. Today I suppose he’s a villain for having made tobacco popular in England, one of many things for which James I hated him and for once not without reason. (If you wonder why James regarded himself as a highly intelligent man and a skilled controversialist, you should read his “Counterblaste to Tobacco” which shows him at his best; a man who could write “A custome lothsome to the eye, hatefull to the Nose, harmefull to the braine, dangerous to the Lungs, and in the blacke stinking fume thereof, neerest resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomelesse” cannot have been entirely without virtues.)

As for Raleigh, he was brave, gallant and dashing. But also I think somewhat slippery, not a man on whose word it might be safe to rely. His career had many ups and downs and not everything bad that happened to him was undeserved. But on balance there are two things for which I cherish his memory, along with a throwaway line in a book I read in my teens saying when Raleigh was sent with troops to Ireland to deal with a revolt there were already British soldiers stationed there to tell the newcomers there was “no bread, no beer, no money and the butter was hairy”.

One was his insistence during his treason trial on the right to summon witnesses, not then a feature of English law. It failed, but his words still ring: “[Let] my accuser come face to face, and be deposed. Were the case but for a small copyhold, you would have witnesses or good proof to lead the jury to a verdict; and I am here for my life!" The other was his principled stand in debate on a harsh bill aimed at Protestant dissenters, informed perhaps in part by his own experience of persecution under the Catholic Bloody Mary. As Catherine Drinker Bowen describes it in her wonderful biography of Edward Coke, The Lion and the Throne, “Laws that punished the fact, he [Raleigh] could approve. But laws which punished a man’s intention he considered hard. Were juries henceforth to be ‘judges of men’s intentions, judges of what another means?’ And on such judgement, were they to take life and send into banishment?”

His own career ended badly and I’ll bet being one-upped by him at court was as much fun as Edward Blackadder made it sound (see the second series episode “The Potato”). But he was a true Englishman and never more than in his spirited defence of liberty sheltered by just law.