It happened today - November 7, 2015

Everyone knows that the American Republican party symbol is an elephant. But why?

Everyone knows that the American Republican party symbol is an elephant. But why?

The short answer is that on Nov. 7, 1874, cartoonist Thomas Nast drew it as one in Harper’s Magazine. I suppose it beats a donkey. But why did he choose an elephant and why did it stick?

For that matter, why a donkey for the Democrats? That one is more of a political classic. It dates back to 1828, when his adversaries called Andrew Jackson a jackass and, instead of groveling, apologizing or fleeing, he defiantly adopted it as symbol of determination on his campaign posters.

An amazing number of political emblems originate as abuse that fails because its targets are not frightened, including labels like Whig and Tory. Still, if you had a choice you’d probably not want a braying, stubborn, generally undistinguished animal. Which brings us back to the elephant. Sort of.

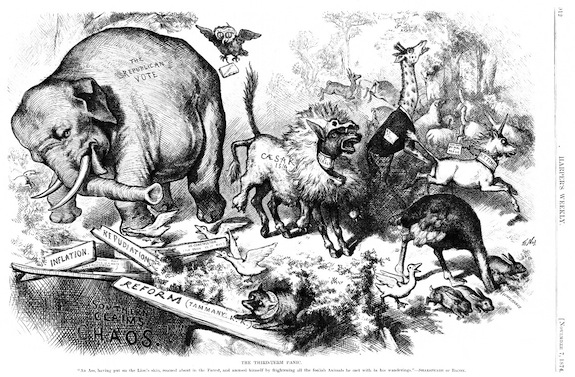

Nast’s 1874 cartoon showed a donkey dressed in a lion’s skin scaring animals at the zoo including an elephant labeled “The Republican Vote.” (Connoisseurs will know that 19th and 18th-century political cartoons tended to be festooned with labels that seem to me to prove they weren’t really funny; jokes that need elaborate explanation have missed their mark.) So I guess the idea was that it was unreasonably timid for its size or something.

The odd thing is that it stuck. Nast was a skillful and influential cartoonist (among other things, his drawings of New York City political bigwig “Boss” Tweed in a convict outfit helped bring the man down and, indeed, after he fled justice, led to his identification by Spanish police who recognized him from those cartoons). So I guess he did a good elephant.

He also did a good donkey and helped reinforce its identity as the Democrat. But a key part of the puzzle is that parties, and cartoonists, need emblems to make jokes or create images that communicate a lot without needing elaborate explanation. A singularly wise or dim looking donkey, a bold or frightened elephant, give depth and impact to a political cartoon. In that sense it’s analogous to the persistence of “Grit” and “Tory” in Canada not for visual but for typographic reasons: They fit readily into print headlines. (For all you kids out there, there used to be these things called newspaper that were on actual paper and you had to pick them up and couldn’t be retweeted.)

Likewise with nations: John Bull or a lion for Britain, an eagle or Uncle Sam for the United States, a bear for Russia. And um a beaver for Canada. What, were we late to the emblem handout? Yeah, we’ll take the buck-toothed terror of trees in wet areas. Cool. And where are the animal emblems for our parties?

Even Teddy Roosevelt’s relatively short-lived Progressive Party got to be the “Bull Moose” party and we have plenty of meese. Our cartoonists need emblems. Can’t someone stick an animal on the parties?

OK, I can’t think of suitable ones off the bat. And a bat wouldn’t be ideal for those who favour any given party. But if Republicans can be elephants and Democrats donkeys to general satisfaction without too much quarreling over the logic, perhaps we could throw a few classic Canadian emblems into a hat, a polar bear, a Canada goose, an elk and stuff and have a “draw”.

Otherwise we keep having to choose politicians sufficiently remarkable-looking, in good ways or bad, to be prime caricature material. Which we’re doing OK at for the most part. But I’d still go for animals and, luckily, the beaver is already taken.