The Pork and Beans War

For today we’re going to skip battles… and go right to a war. The Aroostook War, specifically. Which is a bit of a letdown for military buffs because there weren’t any battles. Instead this squabble among lumberjacks in New Brunswick and Maine, sometimes called the “Pork and Beans War”, ended in the Webster-Ashburton Treaty signed August 9, 1842, in which two major powers with a history of belligerence cheerily tossed bits of land at one another and made permanent peace. And maybe you shouldn’t, but you do get points for guessing they’re democracies.

For today we’re going to skip battles… and go right to a war. The Aroostook War, specifically. Which is a bit of a letdown for military buffs because there weren’t any battles. Instead this squabble among lumberjacks in New Brunswick and Maine, sometimes called the “Pork and Beans War”, ended in the Webster-Ashburton Treaty signed August 9, 1842, in which two major powers with a history of belligerence cheerily tossed bits of land at one another and made permanent peace. And maybe you shouldn’t, but you do get points for guessing they’re democracies.

Of course most of you knew all about this deal already, right? Under President John Tyler (what, you didn’t know about him?) it tidied up some lingering questions about the border between the rising United States and what was left of British North America after that Revolutionary War unpleasantness and the Thing of 1812. It established the border from Lake Superior to Lake of the Woods, ran things along the 49th parallel to the Rockies, agreed on some extradition issues, carved out a small lump of Canada to include a fortification mistakenly built on the wrong side of the border and amusingly dubbed “Fort Blunder”, later the impressive Fort Montgomery and now the crumbling thing for sale on eBay (I am not making this up, but it will set you back nearly $3 million before fees and incidentals), set up shared use of the Great Lakes and for a kicker called for a final end to the slave trade on the high seas. Especially odd given that the United States was, you know, the slave nation.

What’s also odd is that these various expressions of pious intent to live together were actually sincere at the time and have worked ever since, before and after Canada the place became Canada the nation. It may not seem odd since we’re used to it, overheated 1970s rhetoric about American imperialism notwithstanding. But it is odd. Flowery diplomatic language is generally followed by treacherous blows.

Not here. And that raises the vexed question, entirely suitable for a university exam, of whether democracies are different in foreign affairs. The question is more complex than it seems and so is the answer. In the first place, if you say “yes” you could mean they’re more virtuous, more feeble, both or neither because you could mean they’re more feeble before a crisis and more dynamic afterwards. If you say “no” you’re presumably a Realpolitiker of the Tallyrand-Nixon school who believes nations have no friends, only interests. Which sounds like Kissinger because he said it, and de Gaulle ditto, but comes from Palmerston for whom the British Foreign Office cat is now named. And in this view, which Nixon also espoused with remarkable eloquence, consistency and effectiveness, foreign affairs is akin to chess, a game in which players with competing goals all share the same understanding of the rules and the strategy unless they are chumps. The hard part here is that democracies might be more likely to elect chumps than dictatorships to have them emerge from the proverbial dogs fighting under a carpet.

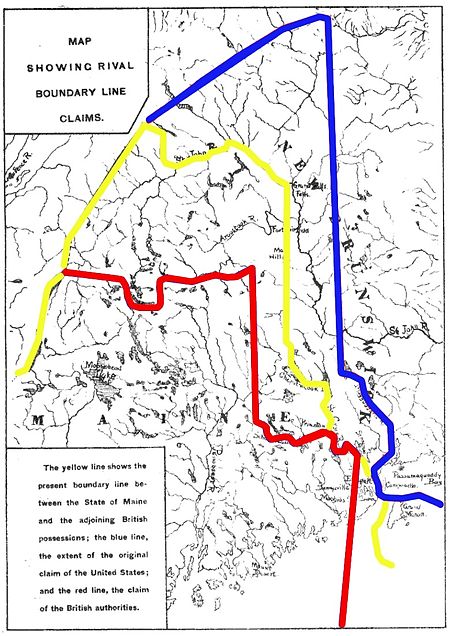

The other hard part is explaining how democracies fumble in the face of tyrannical threats and then, at least if they are Western democracies, crush them into dust. And how it is that democracies interact with one another differently than they do with tyrannies or tyrannies do with one another. Manifestly Great Britain and the United States had very similar geopolitical objectives by the 1840s and even the 1820s and what’s more, their more enlightened statesmen knew it even if they sometimes had to deal with an irate populace in the process. (Webster himself sold his treaty with Ashburton partly on the basis of a map of dubious provenance supposedly drawn by Ben Franklin showing the border he’d agreed to as the proper one.) But why did they have similar objectives?

Geography and economics might explain some of it. But it clearly goes deeper. It was said that no two nations with full adult manhood suffrage ever fought a war until Clinton’s showdown with Milosevic. But one exception does not disprove a rule, and clearly Yugoslavia’s situation was abnormal. (And if you’re thinking War of 1812, don’t forget Britain had severely restricted suffrage in its days of glory and the United States mostly denied blacks the vote even if they were not slaves.) Democracies and tyrannies may agree that, say, Gibraltar controls the western end of the Mediterranean. But what they try to do about this knowledge, and how, differs broadly.

You could not get a Webster-Ashburton Treaty, not just the bit of paper but the results, between Hitler and Stalin, or two bemedalled and sunglassed Third World thugs, or between a democracy and any of the above. So there is something different.

Next question: What is it?

Take your time.