Theory in practice

Here’s a cool thing about the founding of the United States. The social contract.

Here’s a cool thing about the founding of the United States. The social contract.

You know, that fiction by which political philosophers like John Locke explore the fundamental question of why and how we form societies with governments, and what powers the state does or does not possess based on the purpose and process by which we create them. I’m all for this sort of analysis, especially when it is John Locke doing it. But it’s just an imaginative way of thinking about the problem, people having formed themselves into societies long before there was writing or political science. There is no “social contract” signed by Neanderthals or somebody using red ochre on a buffalo hide unearthed in a cave in southern France.

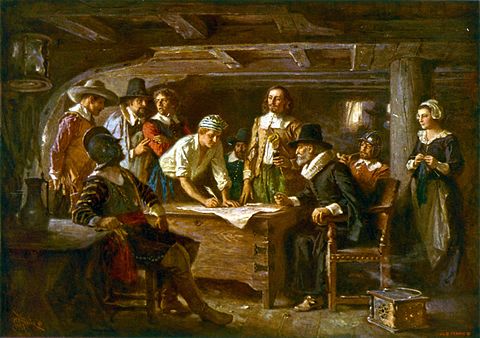

Unless, of course, you’re the Pilgrims. These early migrants to what later became Massachusetts were an obscure sect within Puritanism with limited actual impact on the colony and later the nation. But when they were about to disembark from the Mayflower, on November 21 1620 (on the old calendar November 11) they signed the following document:

“In the Name of God, Amen./ We whose names are underwritten, the loyal subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord, King James, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France and Ireland King, Defender of the Faith, etc./ Having undertaken, for the Glory of God, and advancement of the Christian Faith and Honour of our King and Country, a Voyage to plant the First Colony in the Northern Parts of Virginia, do by these presents solemnly and mutually in the presence of God, and one of another, Covenant and Combine ourselves together into a Civil Body Politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact, constitute and frame such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions and Offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the Colony: unto which we promise all due submission and obedience. In witness whereof we have hereunder subscribed our names at Cape Cod the 11 of November, in the year of the reign of our Sovereign Lord, King James of England, France and Ireland the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth Ano. Dom. 1620.”

The Pilgrims are the only people I know who actually did this. On the eve of building a new society physically, that a disparate group from various parts of England that were currently the frequently very sea-sick inhabitants of a ship (the crew dubbed them “puke-stockings” which pretty much says it all including that some slang words are very durable) made a written covenant that created the body politic and they didn’t get it from the king. They did it themselves. The Mayflower Compact bowed down to James I but didn’t actually ask his permission. And they pledged allegiance to the covenant not the king.

In some sense all Constitution-making, if done through popular approval, has this quality. But that sort of Constitution-making is a modern habit and it all traces back to the Pilgrims. And before they more or less vanished into history, despite their place in folklore, and despite the misuse of the power to make new Constitutions in places like Revolutionary France or the U.S.S.R. they gave us a great gift by showing us the people actually constituting themselves and asserting their right to make, control and if necessary abolish governments that arise through the consent of the people when they make the very real social contract.