“Oh Burr, oh Burr, what has thou done,/ Thou has shooted dead great Hamilton!/ You hid behind a bunch of thistle,/ And shooted him dead with a great hoss pistol!” – Anonymous, 1804

“Oh Burr, oh Burr, what has thou done,/ Thou has shooted dead great Hamilton!/ You hid behind a bunch of thistle,/ And shooted him dead with a great hoss pistol!” – Anonymous, 1804

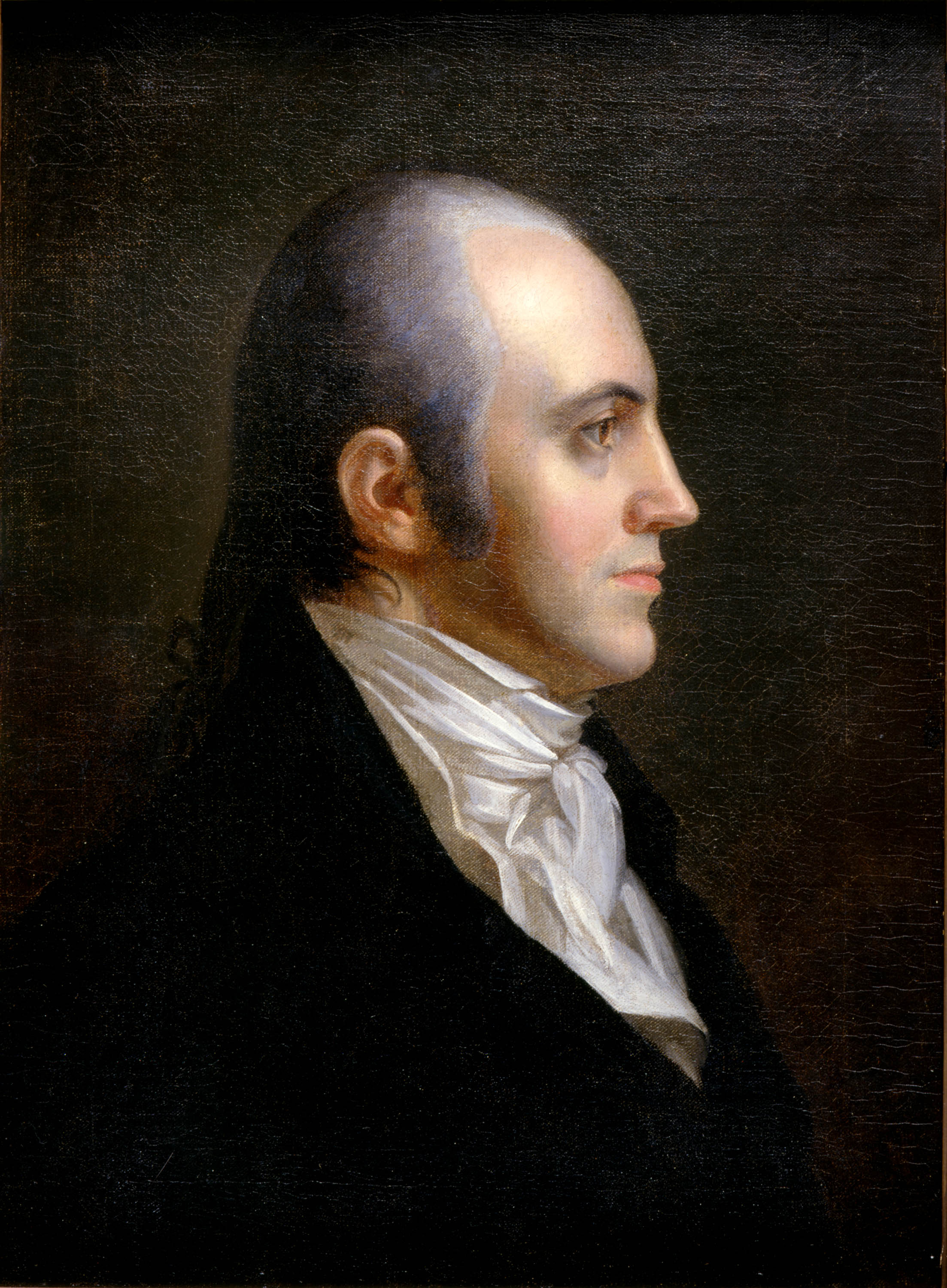

Actually the loathsome Aaron Burr didn’t hide behind a bunch of thistle on July 11 of 1804. He shot Washington’s chief revolutionary war military aide, and later Secretary of the Treasury, in a formally staged duel. But most “duels” were settled without lethal violence; Hamilton himself had been in 10 previous ones without a shot being fired. And Burr’s reputation, such as it was never recovered.

The amazing thing is that Burr was, at the time, vice-president of the United States and could very easily have been president. He was Jefferson’s running mate in 1796 and again in 1800 (here as elsewhere Jefferson showed an appalling lack of judgement). And here you must forgive a digression in to electoral mechanics to understand what happened.

Because the U.S. Constitution did not foresee, and its Founding Fathers did not want, political parties, the original electoral system gave each member of the Electoral College two votes for president, with the top two vote-getters becoming president and vice-president respectively.

It worked fine when George Washington was the universally acknowledged best choice; his unofficial running mate John Adams came comfortably second twice. But in the genuinely contested 1796 election, supporters of both Adams and his rival Thomas Jefferson realized that at least one of their Electors must not vote for their guy and his running mate or they’d end up tied.

This got people thinking of the mischief that could be achieved through strategic use of the second ballots. First the Jeffersonians, realizing they were going to lose either way, started hatching convoluted schemes to have some of their Electors cast one vote for Jefferson and the other for Adams’ running mate Thomas Pinckney so Pinckney not Adams would finish first and end up president.

Adams’ Federalists began counter-plotting, thinking of ways to cast sufficiently fewer votes for Pinckney than Adams that cunning Jeffersonians couldn’t put him over the top. It got out of hand, as these things will, and the unfortunate result when the dust had settled was that so many Federalists voted for Jefferson to undermine Pinckney that Jefferson came second and became Adams’ vice-president, an arrangement distressing to both.

In 1800 something even worse happened. The Federalists kept it simple, having all their Electors vote for Adams and all but one for his running mate Charles Pinckney, with a single vote going to another distinguished federalist. But the Jeffersonian Republicans somehow fumbled their attempt to carry out the same elementary plan, and Burr and Jefferson wound up tied.

Enter Hamilton. The result of the tie, constitutionally, was to send the election to the House of Representatives then sitting, the one elected in 1798, controlled by the now-defeated Federalists. Voting by state not by individual representative, it deadlocked for a week, voting 35 times and each time giving Jefferson a majority (8 states) but not the 2/3 needed to settle it. Finally Hamilton, convinced that Burr was more dangerous than Jefferson because the latter had wrong principles while the former had none, persuaded his colleagues to make Jefferson president. (The voting system was fixed by the 12th Amendment in time for the 1804 contest, creating separate presidential and vice-presidential votes for each member of the Electoral College.)

Clearly giving the presidency to Jefferson in 1800 was the right decision. It reflected the popular will (except that in 1800, had slave states not been overrepresented electorally, Adams would have won). And Burr really was worse than Jefferson.

So bad that, as Burr’s relations with Hamilton deteriorated after this incident, partly due to the admittedly prickly Hamilton’s outspoken criticisms, Burr challenged him to a duel, refused to have the matter settled honorably without bloodshed, and killed Hamilton.

Burr was charged with murder but never tried. He then went west to try to repair his shattered fortunes in land schemes so shady that Jefferson ended up having him arrested and tried for treason. He was acquitted, but left the United States in 1807, returning quietly and penniless in 1811, changed his name, practised law, and died in 1836, the same day his second wife divorced him for squandering her money in a final round of land speculations. About the only good thing you can say about the latter part of Burr’s life is that it was quietly rather than spectacularly disgraceful. And thank goodness he was never president.

I say it though I’m no fan of Thomas Jefferson. He was a man of utopian abstractions, unreasonably sympathetic to the French Revolution, reckless geopolitically and an absolute and hypocritical wretch on race. But there was a certain noble grandeur even about his errors. And it is striking in this context to reflect that, in its formative decades, the fledgling American Republic did not have a single truly bad president.

Some were undeservedly unpopular, like John Adams and his son John Quincy Adams. Others were undeservedly popular, especially Jefferson. But not one of the first eight were squalid, vicious or pitiful. Burr was all three, irremediably.

Were it not for Hamilton’s great achievement in putting aside his partisan and personal antipathy for Jefferson and securing him the presidency, the U.S. might have suffered untold harm from having the genuinely dreadful Aaron Burr in the White House. It’s bad that he killed Hamilton. But he might have done far worse.

Seventy-five years ago, on July 10 1940, the German Luftwaffe began one of the pivotal battles in world history, the Battle of Britain. Hundreds of planes attacked shipping in the English channel as the preliminary effort to draw out the Royal Air Force, destroy it, and thus keep the Royal Navy away from the planned “Operation Sealion” invasion of the United Kingdom.

Seventy-five years ago, on July 10 1940, the German Luftwaffe began one of the pivotal battles in world history, the Battle of Britain. Hundreds of planes attacked shipping in the English channel as the preliminary effort to draw out the Royal Air Force, destroy it, and thus keep the Royal Navy away from the planned “Operation Sealion” invasion of the United Kingdom. On this day in history, back in 1850, President Zachary Taylor died of cholera. Sic transit lack of gloria mundi, you may say. Or just “Who?!?” But think for a moment what might have happened otherwise.

On this day in history, back in 1850, President Zachary Taylor died of cholera. Sic transit lack of gloria mundi, you may say. Or just “Who?!?” But think for a moment what might have happened otherwise. On July 8 back in 1994 Kim Il-sung died. Sort of. I mean, his body perished. His ideas had long predeceased him. But the Constitution of North Korean declared him “Eternal President” on September 5, 1998. So that’s one less thing.

On July 8 back in 1994 Kim Il-sung died. Sort of. I mean, his body perished. His ideas had long predeceased him. But the Constitution of North Korean declared him “Eternal President” on September 5, 1998. So that’s one less thing. On this day a decade ago, suicide bombers set off three bombs on the London subway and one on a bus during rush hour. The bombers killed 52 people, plus their own wretched selves, and injured over 700 in Britain’s worst terrorist incident since the 1988 Lockerbie bombing, its first ever suicide attack, and the most serious attack on British soil since World War II. And yet it accomplished nothing.

On this day a decade ago, suicide bombers set off three bombs on the London subway and one on a bus during rush hour. The bombers killed 52 people, plus their own wretched selves, and injured over 700 in Britain’s worst terrorist incident since the 1988 Lockerbie bombing, its first ever suicide attack, and the most serious attack on British soil since World War II. And yet it accomplished nothing. On this date in 1776 the American colonies did not declare their independence. It actually happened on July 2. But it came to be celebrated on the 4th and rightly so.

On this date in 1776 the American colonies did not declare their independence. It actually happened on July 2. But it came to be celebrated on the 4th and rightly so. On July 3, 1863, the Union won the Civil War. Or perhaps one should say the Confederacy lost it. Or perhaps neither.

On July 3, 1863, the Union won the Civil War. Or perhaps one should say the Confederacy lost it. Or perhaps neither. , partly because we were just at the battlefield last month as part of our Magna Carta documentary (if you’re wondering what the connection is, watch the documentary when it appears.) And I fantasize about being among the generals trying to talk Lee out of ordering the attack, including his right-hand man James Longstreet, and saying “Sir, if you held that high ground and the Union commander ordered his men to advance across all that open ground exposed to superior artillery fire, you would consider him unfit to command, would you not?”

, partly because we were just at the battlefield last month as part of our Magna Carta documentary (if you’re wondering what the connection is, watch the documentary when it appears.) And I fantasize about being among the generals trying to talk Lee out of ordering the attack, including his right-hand man James Longstreet, and saying “Sir, if you held that high ground and the Union commander ordered his men to advance across all that open ground exposed to superior artillery fire, you would consider him unfit to command, would you not?”