Just over three centuries ago, on Oct. 23 1707, the Parliament of Great Britain first met. If that sounds odd, it’s because it was the successor to the Parliament of England and, in a very loose sense, that of Scotland, following the 1706 Acts of Union passed in both parliaments. It sat until 1801, when the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland came into existence. And a fine thing it was too.

Just over three centuries ago, on Oct. 23 1707, the Parliament of Great Britain first met. If that sounds odd, it’s because it was the successor to the Parliament of England and, in a very loose sense, that of Scotland, following the 1706 Acts of Union passed in both parliaments. It sat until 1801, when the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland came into existence. And a fine thing it was too.

It is instructive to compare the flourishing of representative institutions in England with their withering in Europe as the Middle Ages ended. By the 16th century even a terrifying bully like Henry VIII did not dare undertake major initiatives without parliament, whereas in France a leading political theorist, law professor and member of the Paris Parlement, Jean Bodin, wrote “When edicts are ratified by Estates or Parlements, it is for the purpose of securing obedience to them, and not because otherwise a sovereign prince could not validly make law” while in 1527 the president of the highest court assured king François I “we do not wish to dispute or minimize your power; that would be sacrilege, and we know very well that you are above the laws.”

Indeed, the French Estates General did not meet at all from 1614 until the collapse of the ancien régime. Meanwhile the English parliament confirmed kings, deposed them if they were tyrants, protected rights and ensured that no one was above the law.

As for Scotland, well, the truth is that even it had a parliament quite unlike that of England. As James I complained on becoming king of England as well as Scotland (where he was James VI), the parliament in Edinburgh listened to him “not only as a king but as a counselor. Contrary, here, nothing but curiosity from morning to evening to find fault with my propositions. There, all things warranted that came from me. Here, all things suspected!” And indeed the Scottish parliament ended as it had lived, in a supine and crooked act of acquiescence to instructions from above to dissolve itself.

In this, as in many other things, the Scots benefited enormously from the Act of Union. They acquired representative government that really did limit rulers, were incorporated in the mighty polity that launched the Industrial Revolution, founded the Anglosphere, ruled the waves, and dominated the globe culturally.

The union with Ireland from 1801 was obviously never as happy or successful, leading to the separation of the Irish Free State in 1922 and the ongoing “troubles” in Ulster. But if Daniel Hannan is to be believed in Inventing Freedom, the relationship between the rest of Ireland and Britain has never been closer or happier. If only the same could be said of Scotland.

That there should now be such petty discontent with Great Britain north of the border, and such lukewarm defence of it on both sides, is a tragedy and a pathetic one. I blame the British elite, which seems to me not to cherish its history and its traditions and have put up such a feeble fight against Scottish separatism.

The summoning of the first Parliament of Great Britain should be cause for celebration. If only there were celebrants.

On October 22 of 1899, an obscure academic printing press released the first advance copies by an obscure Vienna doctor of an obscure volume that changed nothing including his bank balance as it took years to sell the first 600-copy print run. But then it changed everything, as pop interpretations of Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams swept popular culture and helped convince us that everything is relative, which is the signature tune of the post-modern era.

On October 22 of 1899, an obscure academic printing press released the first advance copies by an obscure Vienna doctor of an obscure volume that changed nothing including his bank balance as it took years to sell the first 600-copy print run. But then it changed everything, as pop interpretations of Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams swept popular culture and helped convince us that everything is relative, which is the signature tune of the post-modern era. OK, I don’t like Henry VIII. I haven’t even tried very hard. I was frightened by a Masterpiece Theatre biography when I was a child (the line one courtier uttered on leaving the king’s deathbed, “How can life bear to linger in that rotting hulk?” still haunts me) and never quite got over it. But he was not a likeable man, and he was dangerous, a really bad combination.

OK, I don’t like Henry VIII. I haven’t even tried very hard. I was frightened by a Masterpiece Theatre biography when I was a child (the line one courtier uttered on leaving the king’s deathbed, “How can life bear to linger in that rotting hulk?” still haunts me) and never quite got over it. But he was not a likeable man, and he was dangerous, a really bad combination. On this date back in 439 the Vandals under their chief/king Geiseric took Carthage. And, one imagines, left the place quite a mess.

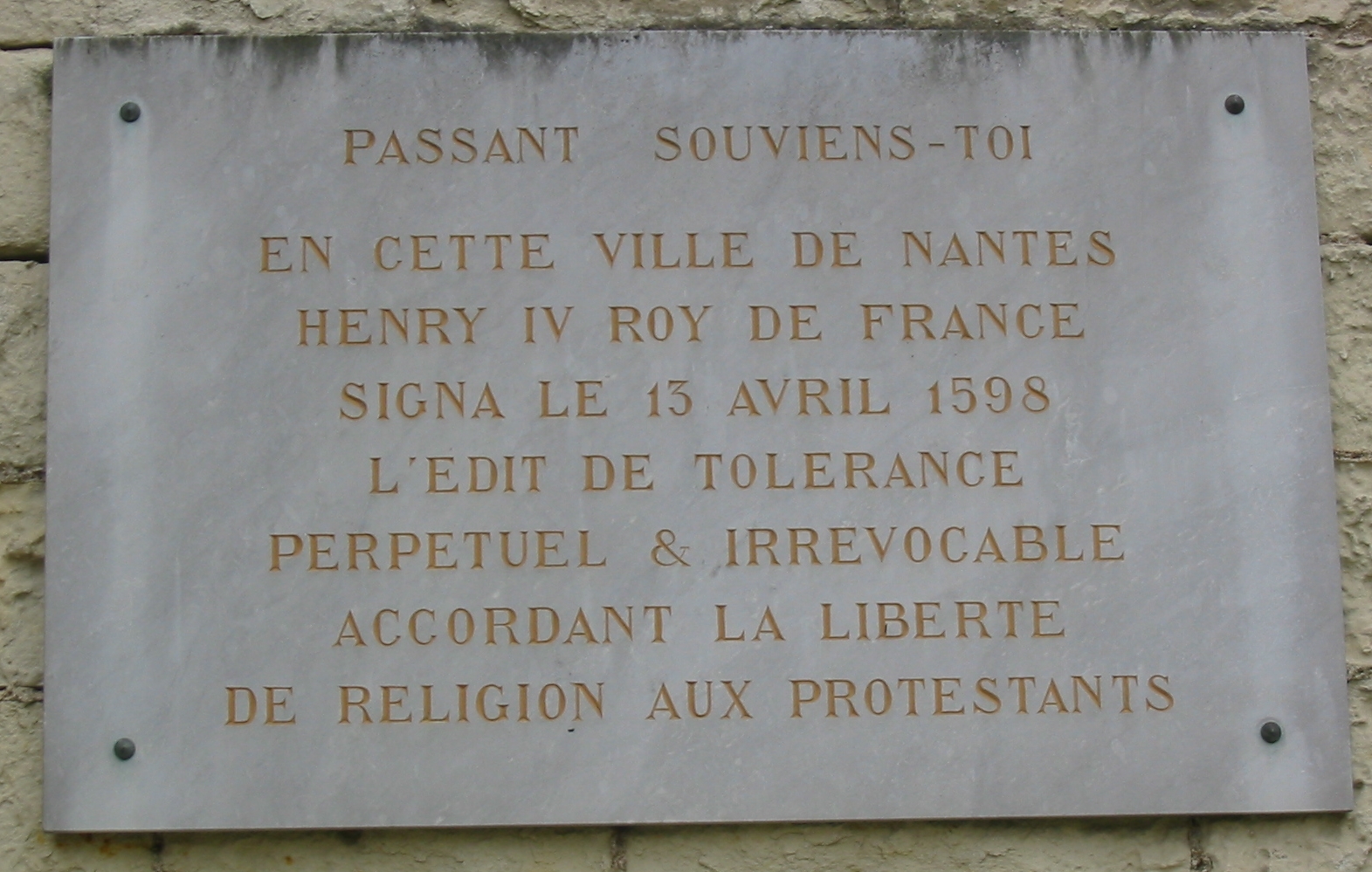

On this date back in 439 the Vandals under their chief/king Geiseric took Carthage. And, one imagines, left the place quite a mess. Well, it was good while it lasted. Sort of. But October 18 is the anniversary of the 1685 revocation of the Edict of Nantes promising toleration to French Protestants, promulgated in 1598 by Henri IV. And the bad thing is, no one was really surprised. Tolerating religious diversity was something French rulers knew in their heads was a good idea. But somehow they never believed it in their hearts.

Well, it was good while it lasted. Sort of. But October 18 is the anniversary of the 1685 revocation of the Edict of Nantes promising toleration to French Protestants, promulgated in 1598 by Henri IV. And the bad thing is, no one was really surprised. Tolerating religious diversity was something French rulers knew in their heads was a good idea. But somehow they never believed it in their hearts. Sometimes you lose a battle and win the war anyway. George Washington had a talent for it. But it’s not what happened to “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne who lost the Battle of Saratoga. Instead, on October 17, 1777 he was obliged to surrender his forces to American Revolutionary general Horatio Gates in a defeat that convinced the French the rebels could win and brought them in on the American side with decisive effect.

Sometimes you lose a battle and win the war anyway. George Washington had a talent for it. But it’s not what happened to “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne who lost the Battle of Saratoga. Instead, on October 17, 1777 he was obliged to surrender his forces to American Revolutionary general Horatio Gates in a defeat that convinced the French the rebels could win and brought them in on the American side with decisive effect. On October 16, 1859, John Brown and a small militant band seized the United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry in Virginia, seeking arms with which to trigger a slave revolt. I confess to being conflicted about it. I find it hard not to sympathize with Brown’s raid, and impossible to sympathize with it.

On October 16, 1859, John Brown and a small militant band seized the United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry in Virginia, seeking arms with which to trigger a slave revolt. I confess to being conflicted about it. I find it hard not to sympathize with Brown’s raid, and impossible to sympathize with it.