If you’ve been following our projects on reclaiming Canada’s heritage, especially the Magna Carta documentary, you know that medieval England was highly unusual in its effective protection of human rights. Including the rights of women.

Racial bigotry wasn’t really an issue in part because virtually everybody was white. But the Middle Ages didn’t draw invidious distinctions on the basis of skin colour to the extent that people then encountered or noticed it. Women had more rights then than in the Renaissance, though fewer than in the Dark Ages, again especially in England where the rule of law has existed from time immemorial in remarkably robust form. Slavery was fast being abolished. It was a remarkable time and place. Unless you were Jewish.

There weren’t many Jews, if any, in Saxon England. They were brought over by the Normans, particularly to serve as moneylenders. No, I’m not stereotyping Jews. Quite the reverse. They were placed under such strict legal limits, or left so dismally outside the protection of the laws, that most occupations were closed to them in theory or in practice. And they just weren’t safe scattered among the populace. So they did the few things they could do.

It gets worse. Because Jews could not own land in England, and the crown basically owned them, if someone’s land was seized for unpaid debts to the Jews, it was seized by the state. So the kings not only wanted to borrow money from the Jews, they wanted you to as well, so they could grab it. Naturally people hated the Jews for lending them money, and would have hated them for refusing to do so, and hated them for wanting it back as agreed, and hated them for being used by the king to seize land, and so on and so on.

Thus in York in 1190 an upsurge in anti-Jewish sentiment because of Richard I’s determination to join the Crusades… No. Stop a minute. That sentence sounds unremarkable because we’re all so used to anti-Semitism. But it’s downright weird. The Crusades weren’t even against Jewish rulers or states. And what had the Jews in England to do with whether Richard did or didn’t go on one? Nevertheless, rumours began to circulate that the king wanted English Jews to be attacked because you know what the heck.

Naturally these rumours were seized upon by people who owed Jews money and felt that they shouldn’t have to pay it back because, again, um, we asked them to lend it and they did so now we should keep it or something. One Richard de Malbis in particular used a house fire to stir up a mob, leading the Jews of York to flee to the royal castle there and take refuge in the wooden keep.

Well, one thing led to another, and after the constable left the castle to negotiate with the lynch mob and the Jews were afraid to let him in, he had the sheriff besiege the castle. The king’s own castle. With innocent people seeking refuge inside it.

Ultimately the Jews decided that they were all going to die, and rather than be tortured and mutilated they set the keep on fire and for the most part killed themselves rather than wait for the flames. A few Jews surrendered instead, promising to convert to Christianity, so naturally they were slaughtered.

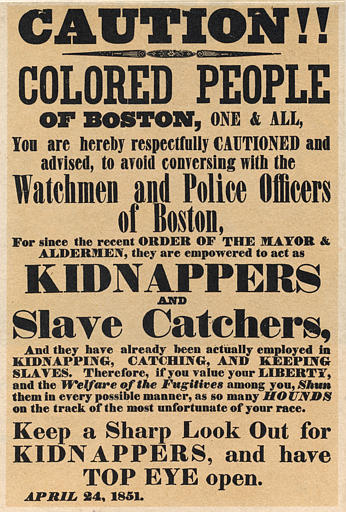

It’s not natural. It is, again, as strange as it is vicious, and while taking full and horrified note of the viciousness one should not let it distract one from the strangeness. What is it about the Jews that causes people to lose their minds and their decency in such a consistent manner? Even blacks, who were subjected to centuries of ghastly racial slavery, were never accused of putting children’s blood into their food, as Jews routinely have been over centuries without, I hardly need add, anything faintly resembling rational grounds for mistakenly thinking they did.

A century after the York pogrom the Jews were expelled from England entirely by Edward I, in 1290, and soon after that they were booted out of France… several times. Spain did the deed in 1492, the same year they completed the Reconquista of the Iberian peninsula from Muslims who, unlike Jews, actually had attacked them. And for what?

Anyway, the Jews were readmitted to England under Oliver Cromwell. Over 300 years later. And gradually they found space within the Anglosphere and ultimately acceptance. Only to have the BDS movement and other such “progressive” causes turn anti-Israel with a degree of willful blindness and hypocrisy to the far worse conduct of its Middle Eastern neighbours that I can only attribute to anti-Semitism.

The fact that anyone who reads history is used to anti-Semitism, and its tendency to break out repeatedly in vicious and hallucinatory forms over and over again in the most unlikely places, should not blind us to the fact that it is as weird as it is hideous.

Something is going on there that demands our attention.