This is a bit of an odd one. For on this date, April 12, 637 AD, Edwin of Northumbria converted to Christianity.

This is a bit of an odd one. For on this date, April 12, 637 AD, Edwin of Northumbria converted to Christianity.

It might not seem odd because we know, as a general fact, that the pagan Germanic inhabitants of southern and eastern England, the fearsome barbarians who had swept aside the remains of Roman Britain, were converted to Christianity. It says so in history books. But how can such a thing have happened?

I mean seriously. As I hinted in the April 8th installment of this series, imagine you’re some monk or cleric in the warm, hospitable Mediterranean area where Christianity has been familiar for half a millennium and established for over three centuries, since Constantine I’s “In hoc signo” moment. And the pope or some such character calls you in and says you’ll never guess, we’re sending you somewhere cold, foggy, unknown and full of people who think a “blood eagle” is funny so you can tell them their religion is rubbish and a dead Jewish carpenter is God.

You respond with a grim declaration that “I am going to die. These people are definitely going to cut bits of me off to satisfy their dreadful gods.” And the pope says oh, don’t worry, the odds are pretty good you’ll drown in a shipwreck along the way or something. Ha ha ha, you reply, and then off you go. And it works.

Huh? It what?

It works. It really works. Instead of mangling you they listen respectfully, weigh the matter, agree that their religion is rubbish, burn their idols and adopt yours.

Reading the Venerable Bede on the subject today we are tempted to laugh it off as naïve propaganda. There’s Edwin of Northumbria (which if you’re trying to remember or figure out where it is, by the way, think “North” and “Humber”; there, that was easy, right, a lot easier than this business with the blood eagles and the dead Jewish carpenter) turning to his advisors and asking what they think, and his priest goes well, you know, sire, you’ve certainly been very devoted to our traditional gods and they don’t seem to have done anything for you, and other members of Edwin’s witan say yeah, that’s true, isn’t it, and then the priest says OK, I’ll burn our idols myself and they get baptised and live happily ever after at least until Edwin is killed in battle and becomes a saint which I guess was a good result for him.

Yeah, right, you say. Especially when you read Bede’s account of an unnamed councillor standing up, brushing off the muck, and saying “The present life man, O king, seems to me, in comparison with that time which is unknown to us, like to the swift flight of a sparrow through the room wherein you sit at supper in winter amid your officers and ministers, with a good fire in the midst whilst the storms of rain and snow prevail abroad; the sparrow, I say, flying in at one door and immediately out another, whilst he is within is safe from the wintry but after a short space of fair weather he immediately vanishes out of your sight into the dark winter from which he has emerged. So this life of man appears for a short space but of what went before or what is to follow we are ignorant. If, therefore, this new doctrine contains something more certain, it seems justly to deserve to be followed.”

Right. Like anyone in the Dark Ages could talk like that, or think like that. Except if they couldn’t, what did happen? How do you explain it? How do we get from marauders who seem to have left the carcasses of half the Celts in Britain for wolves and crows to the reign of Alfred the Great in four centuries?

Just possibly humans have been much the same everywhere and at all times. Just possibly they have had the same fears and anxieties, the same sense that life must mean more than we see in this world, the same odd combination of clinging tenaciously to the familiar and being willing to take a wild chance. And just maybe those pagans evangelized in seventh century Britain didn’t kill all the monks right on the beach precisely because the monks’ story was so bizarre, and their own religion such thin gruel, that they really did react pretty much the way Bede says they did, even coming to jeer and staying to listen.

Alternatively, it may just have been Edwin’s wife Aethelburg, who was evidently very sympathetic to Christianity. Maybe the king took a “happy wife, happy life” approach to his personal affairs and, if so, he is not so removed from us today. Or where we should be, anyway.

However you explain it, one fact remains. It’s totally absurd on the face of it. Bede’s account is absurd because what it describes is absurd.

Except it happened. It really happened. And while any theory of history that treats remarkable events as mundane is unsatisfactory, any theory of history that dismisses them even though they happened is itself a great deal more absurd than the events it waves off because it cannot explain them.

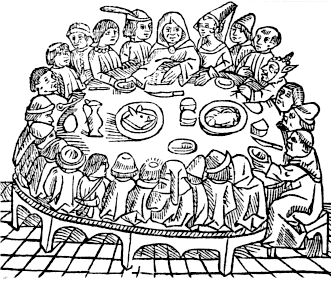

So this is when all that “Whan that aprill with his shoures soote/ The droghte of march hath perced to the roote” got started. Yes, it’s the Canterbury Tales, which I’m sure you knew. And it was on April 17th with its shoures soote that the author, Geoffrey Chaucer, first told them at the court of Richard II in 1397. A very English event… and not just because Chaucer’s verse and prose have struck fear into the hearts of English majors ever since.

So this is when all that “Whan that aprill with his shoures soote/ The droghte of march hath perced to the roote” got started. Yes, it’s the Canterbury Tales, which I’m sure you knew. And it was on April 17th with its shoures soote that the author, Geoffrey Chaucer, first told them at the court of Richard II in 1397. A very English event… and not just because Chaucer’s verse and prose have struck fear into the hearts of English majors ever since.