On May 10 back in 1773 the British got themselves into a mess of hot water with the Tea Act. This measure, a.k.a. 13 Geo 3 c 44 when it received royal assent on that date, was itself the product of some hot Pacific water. But it brewed up an Atlantic-sized helping.

On May 10 back in 1773 the British got themselves into a mess of hot water with the Tea Act. This measure, a.k.a. 13 Geo 3 c 44 when it received royal assent on that date, was itself the product of some hot Pacific water. But it brewed up an Atlantic-sized helping.

The basic problem, or so they thought, was that the East India Company was a victim of its own success, with so much tea in its London warehouses that it was going to go broke in the face of low taxes. Well, also a victim of mercantilism, a cunning plan to enrich a nation by restricting trade of the sort we never seem to hear the end of.

The basic solution, or so they thought, was to allow the East India Company to ship tea directly to the North American colonies rather than having to send it through London, and to export tea duty-free from London. There would still be an import levy when it arrived in America. But the tea would be cheaper for the colonists who would therefore be happy, and profits would be higher for the company which would therefore survive.

Except the best laid plans of mice and men gang aft aglay and when the men are in government the plans aren’t always very well laid to begin with.

In this case two things went wrong.

The first was that the Americans, as true English people, were busily evading excessive taxes by smuggling. So the new, lower duties were actually going to cost them more if they were rigorously collected as the British also intended.

The second was that the Americans, as true English people, were utterly opposed to taxation without representation. So much so that even a tax cut enacted without their consent was resented to the point of active, throw-it-in-the-harbor resistance.

The colonists had already shown mighty opposition to the Stamp Act levies of 1765, taxes imposed without the agreement of their legislatures, which they rightly believed violated a guarantee over 500 years old in Magna Carta against levies without the consent of the kingdom (“nisi per commune consilium regni nostri”). But politics is too often about cunning rather than principle and, as Sir Humphrey Appleby memorably observed, while statesmanship “is about surviving into the next century; politics is about surviving until Friday afternoon.”

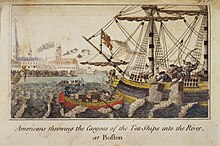

The colonists were not impressed. They took up arms in small, local actions against the landing of tea and famously on December 16 1773 they took up tea chests and gave them the old heave ho into Boston Harbor. The British doubled down on their coercion, suspending local democracy and pushing the colonists into taking up arms on a large scale and ultimately dismembering the first British Empire.

Interestingly, the British in 1778 repealed the tea tax in the Taxation of Colonies Act that said Parliament would not impose any internal taxes, only external ones, which had been the colonial demand a decade earlier. But by then it was too late. The war was under way and it was sovereignty rather than the details of administration that were at stake. For what it’s worth, the Tea Act itself lingered pointlessly on until 1861 long after bad coffee had become the American national drink, the 13 colonies had become the American nation and Britain had been converted from mercantilism to fervent advocacy of free trade. As for the East India Company, it was effectively nationalized in 1773 and survived in this odd hybrid form until the Indian Mutiny of 1857. On the whole it doesn’t seem to have been very good for the Empire.

Nor did the assumption that people in the Anglosphere would sell their birthright for a mess of pottage. The authorities in London cynically assumed a tax cut would buy acquiescence in taxation without representation in Boston, Charleston and points between. To be sure, they even bungled the tax cut. But the deeper point was that in those days, freedom didn’t have a price.

If it does today, we’re getting ourselves into even hotter water than the British did with the Tea Act.