Long live Ramesses II. And he did. Taking the Egyptian throne on May 31 of 1279 BC, he reigned until 1213, dying somewhere around the age of 90, the greatest of all Pharaohs, his queen the famous Nefertari whose tomb contains spectacular paintings including from the Book of the Dead. Look on his works, ye mighty…

Long live Ramesses II. And he did. Taking the Egyptian throne on May 31 of 1279 BC, he reigned until 1213, dying somewhere around the age of 90, the greatest of all Pharaohs, his queen the famous Nefertari whose tomb contains spectacular paintings including from the Book of the Dead. Look on his works, ye mighty…

I will. Because Ancient Egypt fascinates me. It was so, well, monumental, so strangely serene, so long-lasting. The Great Pyramid at Giza, for instance, was the tallest building in the world at 481 feet for nearly 4,000 years from roughly 2560 BC until it was topped by Lincoln Cathedral (525) in 1311 AD. And is the only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World still largely intact.

That’s how long things lasted in Egypt. Remember, while we may casually associate pyramids and Pharaohs, when Ramesses II acceded the Great Pyramid was already 500 years older than Lincoln Cathedral is today. When we were in England last year, and nearly visited Lincoln, we joked that the difference between North America and Britain is that we think 200 miles isn’t far and they think 200 years isn’t old. In Egypt 2000 years isn’t old.

As for Ramesses, he didn’t build pyramids. They were excessively obvious tomb-robber beacons. But he did build, on a massive scale. Temples, monuments, an entire new capital of Pi-Ramesses (dangerous vainglory there) and the famous temple complex at Abu Simba relocated by Nasser so it wouldn’t be flooded when the Aswan Dam created Lake Nasser (speaking of vainglory, but of a cheesy and derivative sort).

The Egypt of the pharaohs continues to fascinate me, and writers of historical fiction, because its message is so massive, confident and utterly inscrutable. Nobody remembers Ptah or Sekhmet today (I was going to say Isis but regrettably it has been appropriated by people all too typical of our times). Yet there it sits, immutable even in ancient ruin, staring calmly like a Sphinx while we rush frantically about.

Indeed, nowadays even the title of tallest building changes hands every few years or, at best, decades. One succeeds another. It was the Empire State Building back in King Kong’s day. Then it was… you don’t know, do you? Apparently for eight years it was the Ostankino Tower in Moscow, which caught fire in 2000. Then came the CN Tower, world-famous in Canada, for 32 years. Then… Go on. Tell me. I defy you. (It’s OK. I didn’t know either. It’s Burj Khalifa in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. 2722 feet. Who cares?

None of these have the dignity of Giza or Lincoln. Our own civilization risks being as mute as Egypt’s without the fascination. So it’s worth remembering that Ramesses, in addition to be sometimes nominated as the Pharaoh of Exodus, really was the Greeks’ Ozymandias. Hence the formerly famous Shelley sonnet about the broken statue or Ramesses that is almost all that remains above ground of his grant new capital in the Nile Delta.

“I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: "Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

'My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!'

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Incidentally Shelley wrote the poem in competition with his friend Horace Smith, today roughly as famous as Seankhibtawy Seankhibra, whose sonnet ends more pointedly for us moderns with:

“We wonder,—and some Hunter may express

Wonder like ours, when thro' the wilderness

Where London stood, holding the Wolf in chace,

He meets some fragment huge, and stops to guess

What powerful but unrecorded race

Once dwelt in that annihilated place.”

If someday someone does gaze upon the ruins of our “Yale box” glass and steel towers and ugly modern sculpture, I very much doubt it will be with the kind of awe that Ancient Egypt’s mute remains still inspire.

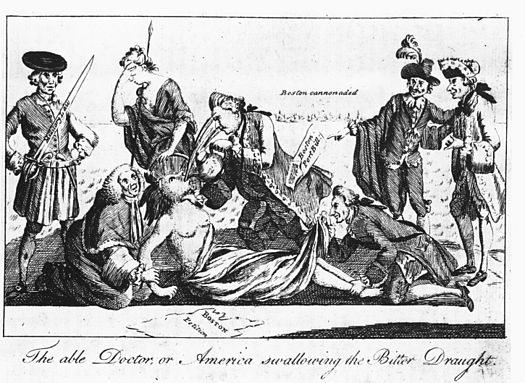

On June 2, 1774, the British Parliament passed the fourth of the Intolerable Acts, the Quartering Act. No wonder the American colonists objected… being English.

On June 2, 1774, the British Parliament passed the fourth of the Intolerable Acts, the Quartering Act. No wonder the American colonists objected… being English.

My first year of It Happened Today features for the month of June is now available as an

My first year of It Happened Today features for the month of June is now available as an