On September 14, 1741, Handel completed his Messiah. I won’t be writing about that in this installment since I already covered it on April 13 of this year, the anniversary of its first performance. But I do bring it up to suggest again that conservatives who think art is for lefties and losers have a look at Brigitte’s C2C piece… while the Messiah blasts out of their stereo.

Instead I’m going to mention that on September 14, 1812, Napoleon captured Moscow. It was quite an achievement and he must have felt pretty pleased with himself. He was on a roll; he’d won his famous victories from Austerlitz to Jena and Wagram. (OK, I didn’t know about the last one, but in 1809 he walloped the Austrian army and the Fifth Coalition disintegrated so it was pretty cool… if you’re Napoleon.)

Now European geopolitics in this period really does resemble a Monty Python sketch. It was of course Britain that had been the prime organizer of various coalitions against Revolutionary and then Napoleonic France that kept disintegrating thanks to that darn Napoleon. But Britain fought Russia from 1807 to 1812 because Tsar Alexander I declared war after the British attacked Denmark on behalf of Sweden.

Then Britain, Russia and Sweden went what the heck are we doing and signed a secret anti-Napoleon treaty in April 1812. Then France and Russia went to war over who would get to mistreat Poland.

There went Napoleon again. Raising another massive Grande Armée, some 650,000 men including 270,000 French and a lot of allies and conquered types, picking up 100,000 Poles along the way despite Napoleon’s refusal to promise them anything, and winning most of his battles while not noticing he was falling for a rope-a-dope.

After three months following Russian armies that were employing a scorched-earth-plus-Cossack-cavalry-harassment plan, the French army finally squared off against the Russians at Borodino and sort of beat them in a bloody confrontation that left at least 70,000 killed or wounded. The French got the battlefield, but the Russian army got away.

So then Napoleon marched into Moscow on the theory that now the Russians had to surrender. It wasn’t actually their capital. That was St. Petersburg at the time (see the September 5 entry). But still, you seize Moscow, they’re meant to surrender.

Instead the Russians emptied the city, released a bunch of criminals, and set it on fire. And Napoleon stood there, with winter approaching, going but but but NO FAIR. Then he turned around and left on the disastrous Grand Retreat that all but destroyed his army; only 27,000 soldiers fit for duty remained by the time he lurched back into Poland.

Being Napoleon, he raised fresh forces and tried again, finally meeting his Waterloo at, well, Waterloo in 1815. And the world was left with two notable things.

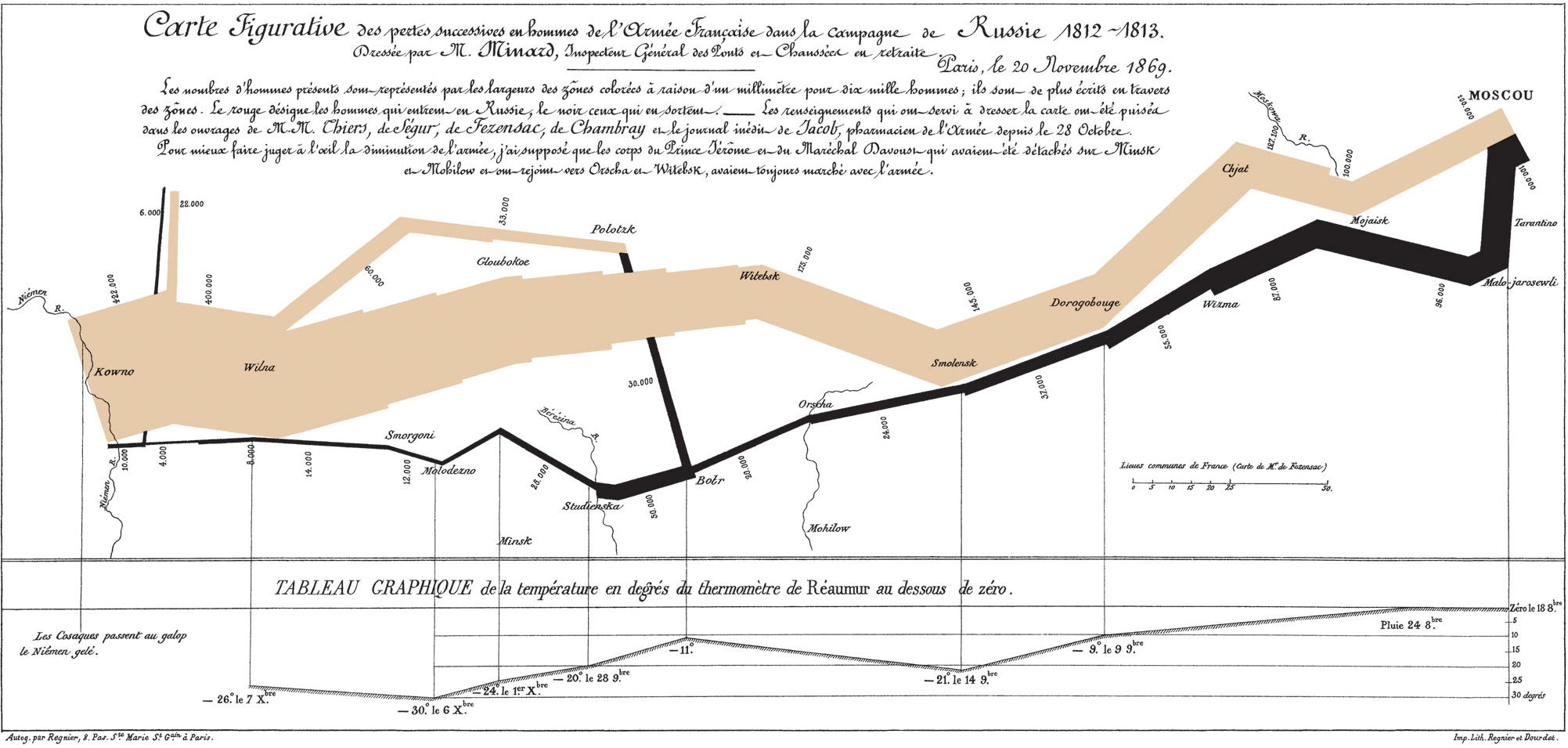

First, one of the greatest graphics of all time, Charles Joseph Minard’s highly imaginative, compact, informative and chilling depiction of the dwindling Grande Armée on its way to and from Moscow (pictured above). Second, one truly reliable geopolitical rule.

Don’t invade Russia.

It often looks inviting. But it never works. (Well, if you’re the Mongols it works for a while but even they faded out.) It’s just too big, too cold, the defenders are too determined and, as Tsar Nicholas I memorably said, “I have two generals who will not fail me: Generals January and February.”

Even a bigshot like Napoleon, who actually captured Moscow and then stood there going Ooops, I should not have done that.