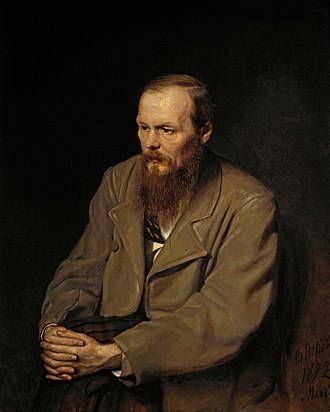

On this date in 1849 the Tsar’s government sentenced Fyodor Dostoevskii to death. It was a true Russian classic.

On this date in 1849 the Tsar’s government sentenced Fyodor Dostoevskii to death. It was a true Russian classic.

In the first place, they arrested and sentenced him for belonging to a revolutionary circle, not for writing unbearably long depressing tormented novels. Not that a man should be sentenced to death for such deeds although if he complains that he’s not enjoying huge commercial success one might justifiably say that the problem might lie with his books at least as much as with his audience.

Nor should he have been sentenced to death for his political views or activities. He held such mad notions as that censorship was bad and so was serfdom. And the “Petrashevsky circle” to which he belonged, partly because they helped him survive despite having no money, was in fact extremely mild in its goals and its, well, I was going to say methods, but really it was just the methods it advocated since it never really got sufficiently organized or energetic to undertake much of anything.

The Tsarist government, painfully aware of the fragility of its superficially omnipotent and seedily magnificent regime, nevertheless reacted harshly to all efforts to develop what we would now call “civil society,” however feeble. So 60 of them were arrested, tried under martial rather than civil law just because, and 15 were sentenced to death, which a higher court stroked its long grey beard and declared to have been a judicial error and they should all be executed. So they were lined up and theatrically pardoned at the last minute by a personal letter from Tsar Nikolai I, who had staged the whole thing.

Instead Dostoevskii and others were, duh, sent to Siberia and treated with such flippant cruelty that it’s amazing anyone survived. But he did, both four years’ hard labour and then even more dangerous compulsory military service, and went on to have a miserable life, sickly, unhappy in love, poor much of the time and a reckless gambler when he had any money.

So now of course he’s a literary giant. But I digress. My point here is that the whole oppression-mock execution affair was a Tsarist classic, witlessly repressive yet unwilling to use genuinely brutal force in a sustained way. The Bolsheviks not only regarded the Tsars as vicious monsters, they somehow convinced the world it was true and that their own regime was, if worse, only marginally so, and at least had better motives.

The truth is that Tsarism was more marked by stagnation than any sort of systematic, energetic effort to make people miserable. The Tsars and their advisors mostly figured that any significant political development would be disastrous and tried to make sure none happened. I don’t endorse this policy, and in the end it failed in a very disastrous way. But I will say this.

If Lenin or Stalin had sentenced a writer to death, or even if they hadn’t, there would have been nothing mock about their execution or mysterious accident. If they sent someone to Siberia, they almost certainly stayed there permanently. And we wouldn’t now have their 38,000-page books to pore over.