In my latest National Post column, I urge the makers of the forthcoming film The Silver Chair to do it faithfully in both senses.

In today's National Post Terry Glavin has another excellent piece on Canada's troubling relationship with China. He's not only very clear on the sinister nature of the government in Beijing and the aggressive style as well as content of its foreign policy. He's also one of the few commentators I know who understands that we are cozying up to an "increasingly decrepit" as well as "belligerent Chinese police state". It is remarkable how wrong the conventional wisdom is about the nature and dynamism of this regime. And Terry is much to be commended for seeing through it.

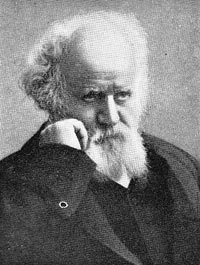

So how about that Pierre Janssen? What, you haven’t heard of him? Why, Pierre Jules César Janssen is the French astronomer who discovered helium, on August 18 1868.

So how about that Pierre Janssen? What, you haven’t heard of him? Why, Pierre Jules César Janssen is the French astronomer who discovered helium, on August 18 1868.

OK, he discovered some other stuff too. He went to Peru to find the magnetic equator, observed a transit of Venus in Algeria, and he studied telluric absorption in the solar spectrum in Italy and Switzerland, which might seem odd since presumably “solar” means it was in the sun, but the sun is a bit hot for direct observation even by an adventurous man.

Which Janssen was. He went wherever you had to in order to study solar eclipses including Siam, as it then was, and Trani, which I don’t even know where it is, and Madras State in India, now Andhra Pradesh. And maybe he enjoyed it and maybe he didn’t. But during the Indian eclipse observations he noticed that the spectral lines (indicating chemical composition) from the sun’s prominences were so bright that they could be observed under ordinary daylight conditions. Which mattered because sometimes an eclipse just didn’t work out. Janssen actually escaped besieged Paris in 1870, during the Franco-Prussian war, by hot air balloon, to observe an eclipse in Algeria and then it got all cloudy.

Janssen was a clever as well as bold and resourceful chap. For instance he also realized it would be good to put observatories in high places so you’d be looking through less atmosphere, which led him to lobby for one atop Mont Blanc and once it was built, at age 69, he climbed up there to make observations, including I suggest the observation that he was one fit guy. But back to helium.

In his results from that 1868 Madras State observation, there was a particular bright yellow line that was eventually determined to indicate a hitherto undiscovered chemical element, the first to be detected off the Earth before being found here (which it was in 1885), helium being of course very light and also extremely non-reactive and thus not hanging around waiting for a scientist to trip over it.

Another scientist, the Englishman Joseph Norman Lockyer, also observed this bright yellow line in the solar chromosphere’s emission spectrum, and he and others worked out that it must be some unknown element, which they named helium for the obvious reason that never struck me until I researched this bit, namely that the Greek word for sun is helios. And without his work, and Janssen’s, no kid would have the brilliant experience of a lighter-than-air balloon on a string or the heartbreak of discovering just what lighter than air means if you let go. (At Disney World they tie weights to the string, in the familiar Mickey Mouse logo shape, which is surely brilliant too.)

So yes, Lockyer gets a lot of credit for helium too. But I still think August 18 is a good date to take a deep breath of the stuff and utter a comically squeaky and high-pitched hip hip hooray for Pierre Janssen.

August 17 is a red-letter day in the annals of dubious achievements. For it was on this date in 1498 that for the first time ever a cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church resigned his office.

August 17 is a red-letter day in the annals of dubious achievements. For it was on this date in 1498 that for the first time ever a cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church resigned his office.

Now you might be thinking, with Benedict XVI in mind, that it’s not an admirable rather than dubious achievement. Someone humbled by their incapacity to perform this exalted office, laying it aside instead of clinging to the pomp and prestige. (Or you might just hate the church and wish they’d all resign, but that’s a topic for another day.)

The problem is, the person who resigned back then was Cesare Borgia. Now clearly he should never have been a cardinal due to his enthusiastic embrace of murderous wickedness, not to mention that he was the illegitimate son of the Pope who made him a cardinal, Alexander VI. (OK, he was just Roderigo Cardinal Borgia when he had Cesare, and probably he didn’t poison people, at least not much, but still.) But Cesare only resigned the post in order to further his and his father’s ambitions by becoming Duke of Valentinois.

It didn’t work. After his father died in 1503, followed after only 26 days by his sympathetic successor Pius III, he was tricked into supporting a deadly family foe Giuliano Della Rovere for the papacy, as Julius II. Four years later Borgia fell into an ambush and was mortally wounded and stripped of everything but a red fig leaf, even the leather mask he wore apparently to hide the ravages of syphilis. Again not the ideal accoutrement for a cardinal.

Cesare Borgia’s career was, apparently, a significant inspiration for Machiavelli’s The Prince. Which might make you question Machiavelli’s judgement as well as his morals except for one point about his infamous book that has been almost universally overlooked lately. The Prince is supposedly the ultimate how-to guide to amoral realism, a kind of Achieving Brutally Cynical Power for Dummies. But in the 18th century it was generally seen, correctly in my view, as a satire, a thinly, even transparently veiled scathing denunciation of power-mad cynics.

If you really were a cynic and tutor to cruel dictators, you would not take as your role model someone whose nasty career ended with ignominious and degrading death in his early 30s. Even if he did at least vacate the cardinalship while vertical, for base motives.

In my latest National Post commentary I say that we must not become used to the government taking forever to buy the wrong military hardware.

If I told you that this is the anniversary of Henry VIII’s 1513 victory over the French at Guinegate, in the Battle of the Spurs, would it provoke yawns at another battle that seems deeply unmemorable? Puzzlement that Henry was fighting the French in France on behalf of the Pope in company with the Holy Roman Emperor? Or would you just wonder what battle in those days didn’t involve spurs?

If I told you that this is the anniversary of Henry VIII’s 1513 victory over the French at Guinegate, in the Battle of the Spurs, would it provoke yawns at another battle that seems deeply unmemorable? Puzzlement that Henry was fighting the French in France on behalf of the Pope in company with the Holy Roman Emperor? Or would you just wonder what battle in those days didn’t involve spurs?

Well, I can settle the last one easily. The name was a cruel jest about the speed with which the French cavalry departed the field, discarding lances, standards and even armour in their haste to escape. Ouch.

As for its consequences, they did include the ill-advised Scottish invasion of England on behalf of their “Auld alliance” French buddies that ended disastrously at Flodden Field. But we all know that the tale of “Henry VIII and his buddy the Pope” story didn’t turn out well in the end. And in fact this “War of the League of Cambrai” also ended badly, with a fairly decisive French victory in 1516, some 17 years before Henry chucked his first wife and the Roman Catholic church while, with absolutely characteristic chutzpah, keeping the title “Defender of the Faith” given him by Pope Leo X in 1521.

Why then am I droning on about it?

Well, for one thing, it’s an opportunity to heap more opprobrium on Henry VIII, who richly deserved it, for his vainglorious strategic overreach. But also to note how longstanding was the English concern not to face a united Europe. There were significant debates about whether to pursue the “blue water” policy generally favoured by the Tories, using the navy to contain whatever continental menace might arise, or the Whig strategy of timely interventions in European squabbles to keep said menace small.

On the whole this strategy worked, to the consternation particularly of the French who aspired for many centuries to be that menace, only to end up the butt of cruel English taunts. There is even a rumour that the peculiar British most rude hand gesture dates all the way back to archers at Agincourt, who were threatened with having their index and middle fingers cut off if captured; regrettably it appears to have no historical foundation. But the English did fight with remarkable skill, backed by remarkable statesmanship over the years, a tribute to the resilient dynamism of free societies.

Henry VIII was still an untrustworthy maniac, though.