In my latest National Post column I lament the latest New Brunswick budget continuing down the boringly disastrous path of deficits today for affordable free money the day after tomorrow... or after the next election... or never.

In what seems truly a bygone era, Fidel Castro seized power in Cuba on February 16 of 1959. Yes, 58 years ago. And a Castro is still in power in this ghastly real-life Autumn of the Patriarch.

In what seems truly a bygone era, Fidel Castro seized power in Cuba on February 16 of 1959. Yes, 58 years ago. And a Castro is still in power in this ghastly real-life Autumn of the Patriarch.

I could say a lot of things about Fidel Castro without getting to anything nice. Like how revealing it is that he would have switched jobs repeatedly while still being the guy you got shot for disobeying. And how typical it is of a regime that for all its yapping about true democracy had no legitimacy that it became dynastic like North Korea. (Mind you his own daughter, from one of his many infidelities, fled the island prison in disguise in 1993 and his own sister opposed him from American exile.) But never mind him.

What I want to do on this dismal anniversary is insult all the leftists who placed such high hopes on him to begin with and then somehow insisted despite everything that he really was a good man and a liberator. Anybody can make a mistake. Even the New York Times in originally hailing him as "the Robin Hood of the Caribbean". But to persist in one, to speak of democracy and human rights and peace in a sanctimonious tone while siding with this seedy brutal villain and denying repeatedly that he was a Communist, or in case he was denying that it mattered if he was one, surely indicates grave defects in judgement.

Especially as it is a habit of the left, from Stalin through Castro to Mugabe and beyond; as Jay Nordlinger memorably put it in National Review back in 1994, "Like an adolescent girl on holiday, the radical Left is always falling in love with some unsuitable foreigner..."

To do it and learn nothing is to double down on nasty folly. Why have so many done it, and not just on the radical left, including our own Prime Minister Justin Trudeau?

For that matter, why are there still Che T-shirts?

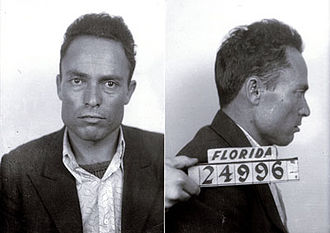

There are a lot of ways to get into the history books. But here’s one you wouldn’t want. On February 15 of 1933, Giuseppe Zangara tried to assassinate president-elect Franklin Roosevelt. Had he succeeded, it would have been the first time anyone was elected president and then died before taking office.

There are a lot of ways to get into the history books. But here’s one you wouldn’t want. On February 15 of 1933, Giuseppe Zangara tried to assassinate president-elect Franklin Roosevelt. Had he succeeded, it would have been the first time anyone was elected president and then died before taking office.

It didn’t happen then, and it hasn’t happened since, something I refrain from mentioning between any election and inauguration lest I should be suspected of trying to jinx the president-elect. As a matter of fact, no one has ever died between being nominated by a major party and the election either. Leaving aside violence, you’d think simply by the odds it would have happened to somebody. (Democratic lion Stephen A. Douglas, one of Lincoln’s opponents in the 4-way 1860 election, did die suddenly less than three months after his victorious rival was inaugurated.)

As for getting into the history books anyway, a dismal footnote to Zangara’s failed attempt is that in the process, standing on a wobbly folding chair and fighting a crowd trying to subdue him, he managed to shoot four other people including Chicago mayor Anton Cermak, who died of his wounds on March 6, two days after Roosevelt’s inauguration. So Cermak becomes "Who was that guy shot by mistake next to FDR?"

Meanwhile Zangara was executed in "Old Sparky," the Florida State Prison’s electric chair, on March 20, justice being swifter in those days. (For what it’s worth, the judge who sentenced him to death called for a complete handgun ban.) And in the process Zangara did make a sort of history.

You see, the rules said prisoners could not share a cell prior to execution but as someone else was awaiting capital punishment he obliged them to expand the "death cell" into the now proverbial "Death Row". It’s not exactly what you put down as your ambition in your high school yearbook. But it beats being the guy assassinated by mistake while the real target wasn’t becoming the first ever president-elect not to make it to Inauguration Day.

Ah, the wonders of the steam age. Including that on February 14 back in 1849, James Knox Polk became the first sitting president of the United States to have his photograph taken.

Ah, the wonders of the steam age. Including that on February 14 back in 1849, James Knox Polk became the first sitting president of the United States to have his photograph taken.

If you’re wondering why he was in office on that date, it’s because prior to the New Deal with its air of constant crisis there was a four-month period between an election and the swearing in of the new president.

Oh, you didn’t mean it that way? You were wondering why somebody called James Polk was ever President? And in his defence I should note first that Polk was elected in 1844 in something of an upset, both as Democratic nominee and then as president, on the pledge to serve only a single term. So he did not run in 1848. (He then enjoyed the shortest retirement of any president, dying of cholera on June 15, 1849.)

Can I say anything else nice about him? Well, he was also elected in part on his pledge to annex Texas which he did, and the United States has generally been better for it. And historians generally credit him with having been a very successful president for having managed to garner support for and pass virtually everything on his agenda. On the other hand, like every other president between roughly John Tyler and James Buchanan, he stands indicted of having failed to halt the drift into bloody civil war.

As for his photo, it’s a somewhat grim affair. But in addition to the expectation that statesmen would look vaguely statesmanlike back then, there was the need to sit very still while primitive film gradually absorbed your image.

It’s a long way from the modern selfie. But in some sense the journey began with Polk.

As I said, the wonders of the steam age.

It is hard to believe that, as late as Edward Coke’s time, it was credible in England to assert that the monarchy was originally founded by Brutus of Troy. (Not et tu Brutus. Another guy.) And yet in Japan it was believed well into the 20th century that their monarchy was founded in the 7th century BC, specifically on February 11 of 660 BC, by Jimmu, a descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu. Also of the storm god Susanoo, by the way. I mean, why stop at one?

It is hard to believe that, as late as Edward Coke’s time, it was credible in England to assert that the monarchy was originally founded by Brutus of Troy. (Not et tu Brutus. Another guy.) And yet in Japan it was believed well into the 20th century that their monarchy was founded in the 7th century BC, specifically on February 11 of 660 BC, by Jimmu, a descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu. Also of the storm god Susanoo, by the way. I mean, why stop at one?

Now it may well be that the Emperorship was in some way established by a guy named Jimmu or something of the sort in or around 660 B.C. Possibly he set up shop in Yamato on February 11, now celebrated as "National Foundation Day" in Japan. After all, there was a historical figure at the centre of the Arthurian legend, a leader of the Romanized Britons after the legions left, despite later embellishments ranging from the inspiring to the downright silly. And Jimmu too may well have been a real person, or modeled on one.

Brutus of Troy? Not so much. I mean, maybe there was a Trojan called Brutus and maybe he even was descended from Aeneas. But however he got into a 9th century Historia Britonum it was not by ship west from Troy, out through the Pillars of Hercules and then north to glory. Nor was "Britain" named for "Brutus". (Nor, I submit, did Aeneas flee to Italy after the sack of Troy and have a son Ascanius who founded Alba Longa. Nor was Brutus descended from Noah’s son Ham. And so on.)

Perhaps you think it childish of me to make sport of these legends. But I do so in order to draw attention to a crucial difference between the governments, constitutions and political cultures of England and Japan. And I do it while acknowledging that the government of Japan seems in many ways to have enjoyed a more organic and harmonious relationship to its citizens than elsewhere.

The thing is, even if people believed the more fanciful tales about Brutus, and gave them some minor weight in legitimizing monarchy in Britain in principle, nobody ever sought to bolster their claim to kingship, or for sweeping powers for the king, by pointing to Brutus. English kings, going back long before Canute, established their claim to the throne by governing well. And governing tyrannically was never justified by the origins of the monarchy even if people sometimes got away with it for a while. At bottom, Brutus was just a piece of colourful embroidery.

Jimmu was not. Or rather, Amaterasu was not. The Japanese Emperor really did claim divinity, via Amaterasu’s grandson Ninigi, supposedly Jimmu’s great grandfather, and a whole lot of his people believed it. Not all, of course. But those who did not kept their mouths shut or someone shut them permanently for them. And because the Emperor was a living god, to the point that when after defeat in 1945 they actually saw the rather unimpressive figure of Hirohito in his ill-fitting suits (because tailors were not permitted to touch a living god even to measure him) and heard his all-too-human voice they were profoundly shocked.

It sounds as silly as Brutus of Troy. But this claim, which incidentally could not be made in a Christian society, made genuine self-government impossible. Canute rebuked courtiers for telling him he was such a favourite of God that he could command the waves. Japanese Emperors would have rebuked and possibly executed courtiers for telling him he was not himself a God. And it matters.

It’s no accident that a regime headed by a living god could launch World War II even though it was neither morally justified nor practically sensible. Who’s going to tell a divinity he’s a belligerent nitwit?

In my latest National Post column I say that identity politics is always divisive no matter how well-intentioned, and it's divisive in large part because it's necessarily false.

It was the eruption onto the main Western stage of an amazing array of musical talent and innovation that showed that Britain was far from exhausted as a cultural force. I do not think it is merely a reflection of my particular advancing age that I call The Beatles, the Who, the Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd, David Bowie and you can pick many others from the Yardbirds to Herman’s Hermits an exceptional flowering of brilliance. And it is certainly not simply a reflection of my own preferences to say that when these acts showed up in an America whose youth were growing sick of sugary pop songs, it changed the world in ways Elvis Presley alone could not have done.

"The Sixties" had many causes beyond a group of talented Brits giving voice and legitimacy to sometimes juvenile frustration. But rock was the backdrop, and once the Beatles and others had touched down and lit things up, nothing could ever be the same.

I would go further and say the Beatles in particular smoothed the path of social change by being so earnest, so "with it" as one could once say without irony or corn, and yet so decent, blowing the whistle on angry radicalism and somehow placing a kindly, steadying hand on the whole counterculture. "You say you want a revolution? … when you talk about destruction/ Don’t you know that you can count me out".

One can point to laws, kings and wars contributing to the upheaval of the 1960s including obviously Vietnam, the "imperial president" Richard Nixon and the civil rights acts. But politicians jump out to lead parades that are already underway, they don’t create or steer them. It was the ambiance of the period that made the anti-war movement so important, not the other way around. And it was the final, long-overdue change of heart among many Americans including Southerners that finally made formal civil rights a social and political possibility.

There were other contributors to the wildness of that decade including darker forces like the Weathermen and of course pharmaceuticals. And here I think "the pill" mattered more than things like LSD or even marijuana. So the Beatles were far from alone. But they were both surfing on and helping shape a massive social movement that changed what politicians could do or duck.

When you saw the way young people reacted to their arrival in the United States, you knew the world was changing radically and laws and kings would have to scramble to keep up with fast-beating hearts.

In my latest National Post column, I argue that if the Liberals were foolish to promise painless, universally popular electoral reform, we were also foolish to believe them that this and other problems were easy to solve just by wishing them away.