Should someone be excused a serious crime because they flipped out? I’m not referring here to a "not guilty by reason of insanity" plea, which I think virtually everyone concedes is sometimes legitimate. I mean the kind of mental imbalance that hits you suddenly and then recedes leaving you quite sane but also quite free.

Should someone be excused a serious crime because they flipped out? I’m not referring here to a "not guilty by reason of insanity" plea, which I think virtually everyone concedes is sometimes legitimate. I mean the kind of mental imbalance that hits you suddenly and then recedes leaving you quite sane but also quite free.

I ask now because February 19 turns out to be the anniversary in 1859 of the first use of the "temporary insanity" plea in the United States. By a Congressman, no less, one Daniel Edgar Sickles, who had killed a son of the composer of "The Star Spangled Banner". You see, Philip Barton Key II was having an affair with Sickles’ wife and Sickles, whose prior conduct was far from blameless (he married a girl half his age, then consorted openly with prostitutes while she was pregnant), got very annoyed and shot him.

It was a different era. The wealthy and privileged Sickles was apparently so popular that visitors streamed to see him in jail where, among other things, he was allowed to keep a gun. But his high-powered lawyers, including Edward M. Stanton who later served as Lincoln’s Secretary of War, convinced the public and the court that he was so angry at his wife’s infidelity that he was not responsible for what he did in his rage.

It may not have helped the prosecution that newspapers subsequently hailed Sickles for saving women from Key. But still, the case troubles me.

In theory I can see that you could take leave of your senses for various reasons including justified anger in ways that diminish or eliminate legal responsibility. But I’m not convinced I understand the difference between being so angry you shoot your wife’s lover and go to jail (or the gallows) and being so angry you shoot him and it’s OK. As a weird footnote, after making his wife’s cheating a huge public issue Sickles publicly forgave her, which evidently upset people a lot more than the original shooting.

Sickles went on to rise to Major General in the Civil War despite his notorious ambition, drinking and womanizing, eventually commanding III Corps, which he so mishandled at Gettysburg that the resulting action cost him his command (as well as his right leg) though not his commission. He spent years after the war arguing that his blunder had actually been a bold and well-advised strategic stroke and in 1897 he received the Congressional Medal of Honor for it, before ultimately dying in 1914 at age 94.

He was, it seems, a man of remarkably poor judgement in his personal and often public life. But the court ruled that his actual insanity was only temporary and absolved him of murder whereas it sounds to me as though in this case at least it was just a singularly spectacular and consequential display of lifelong lack of self-control.

Vermont is not all that controversial. Is it? No. It’s just this rather pleasant New England state with the odd distinction of being among the most Democratic in the United States and the most heavily armed. But precisely because it does not arouse strong passions, it’s interesting to reflect on its admission to the Union on February 18 of 1791.

Vermont is not all that controversial. Is it? No. It’s just this rather pleasant New England state with the odd distinction of being among the most Democratic in the United States and the most heavily armed. But precisely because it does not arouse strong passions, it’s interesting to reflect on its admission to the Union on February 18 of 1791.

Interestingly, that decision was controversial, because Vermont was on land ceded by the French after the Seven Years’ War and at one point New York, Massachusetts and New Hampshire all claimed some of it. By 1770 it was basically New York versus the local staid pious New England rowdies, especially Ethan Allan and his "Green Mountain Boys" who were frankly rather scary vigilantes against New York authority.

Until, of course, the British decided to suppress liberty in their colonies at which point everybody decided to forget their old quarrels and go get George III even though Ethan Allan continued to contest New York’s authority. So here’s the interesting thing.

In the general uprising against British authority, a group of Vermonters gathered in convention declared themselves a sovereign state in 1777. Then they named themselves Vermont, and adopted the first constitution in North America to ban adult slavery. (Eighty-one years later, in 1858, Vermont banned slavery altogether.)

For fourteen years people tried to avoid the awkward topic of whether there was or was not a "Vermont" even though it issued its own money, had a postal service and elected governors. And Congress could not act without New York’s consent under Article IV, Section 3 of the constitution. Finally New York threw in the towel and, after successful negotiations over where exactly the border lay and what compensation was due to New Yorkers whose land titles had been ignored in Vermont, Vermont became the 14th state and (duh) the first new one after the original 13.

What’s interesting here is that Vermont’s claim to statehood rested on two key points. First, the people who then lived there wanted it. And second, they had successfully acted as a state in fact. In short, people bowed to reality.

I’m not saying might makes right. The origins of many nations and subnational jurisdictions give serious pause on grounds of legitimacy, especially in a world that no longer recognises the "Doctrine of Discovery" of places that already had people in them, and is distinctly uneasy with the "Doctrine of Conquest". But the simple fact is that as far back as you can find anything resembling reliable records, land is in possession of those who took it from others including the aboriginals who were in Vermont when Europeans showed up. And sometimes de facto is the best basis you can find for de jure, that is, you agree that Vermont should be accepted as existing essentially because it does exist.

We still hope for perfect justice. We cannot do less. But at times we admit that things are what they are and we must make the best of them.

I do not think a great many people, even in New York, go about today saying Vermont is a fraud and an imposition. But precisely because it does not arouse strong passions, it’s a good test case of our willingness to defy, or accept, what actually does exist in favour of what we wish existed or feel might perhaps have existed under other circumstances.

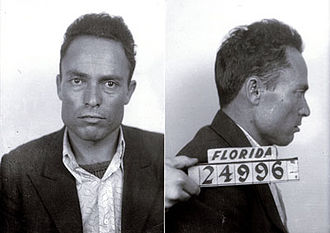

There are a lot of ways to get into the history books. But here’s one you wouldn’t want. On February 15 of 1933, Giuseppe Zangara tried to assassinate president-elect Franklin Roosevelt. Had he succeeded, it would have been the first time anyone was elected president and then died before taking office.

There are a lot of ways to get into the history books. But here’s one you wouldn’t want. On February 15 of 1933, Giuseppe Zangara tried to assassinate president-elect Franklin Roosevelt. Had he succeeded, it would have been the first time anyone was elected president and then died before taking office.

It didn’t happen then, and it hasn’t happened since, something I refrain from mentioning between any election and inauguration lest I should be suspected of trying to jinx the president-elect. As a matter of fact, no one has ever died between being nominated by a major party and the election either. Leaving aside violence, you’d think simply by the odds it would have happened to somebody. (Democratic lion Stephen A. Douglas, one of Lincoln’s opponents in the 4-way 1860 election, did die suddenly less than three months after his victorious rival was inaugurated.)

As for getting into the history books anyway, a dismal footnote to Zangara’s failed attempt is that in the process, standing on a wobbly folding chair and fighting a crowd trying to subdue him, he managed to shoot four other people including Chicago mayor Anton Cermak, who died of his wounds on March 6, two days after Roosevelt’s inauguration. So Cermak becomes "Who was that guy shot by mistake next to FDR?"

Meanwhile Zangara was executed in "Old Sparky," the Florida State Prison’s electric chair, on March 20, justice being swifter in those days. (For what it’s worth, the judge who sentenced him to death called for a complete handgun ban.) And in the process Zangara did make a sort of history.

You see, the rules said prisoners could not share a cell prior to execution but as someone else was awaiting capital punishment he obliged them to expand the "death cell" into the now proverbial "Death Row". It’s not exactly what you put down as your ambition in your high school yearbook. But it beats being the guy assassinated by mistake while the real target wasn’t becoming the first ever president-elect not to make it to Inauguration Day.

Ah, the wonders of the steam age. Including that on February 14 back in 1849, James Knox Polk became the first sitting president of the United States to have his photograph taken.

Ah, the wonders of the steam age. Including that on February 14 back in 1849, James Knox Polk became the first sitting president of the United States to have his photograph taken.

If you’re wondering why he was in office on that date, it’s because prior to the New Deal with its air of constant crisis there was a four-month period between an election and the swearing in of the new president.

Oh, you didn’t mean it that way? You were wondering why somebody called James Polk was ever President? And in his defence I should note first that Polk was elected in 1844 in something of an upset, both as Democratic nominee and then as president, on the pledge to serve only a single term. So he did not run in 1848. (He then enjoyed the shortest retirement of any president, dying of cholera on June 15, 1849.)

Can I say anything else nice about him? Well, he was also elected in part on his pledge to annex Texas which he did, and the United States has generally been better for it. And historians generally credit him with having been a very successful president for having managed to garner support for and pass virtually everything on his agenda. On the other hand, like every other president between roughly John Tyler and James Buchanan, he stands indicted of having failed to halt the drift into bloody civil war.

As for his photo, it’s a somewhat grim affair. But in addition to the expectation that statesmen would look vaguely statesmanlike back then, there was the need to sit very still while primitive film gradually absorbed your image.

It’s a long way from the modern selfie. But in some sense the journey began with Polk.

As I said, the wonders of the steam age.

In 1865 the United States finally abolished slavery. It happened far too late and tragically it happened without abolishing bigotry or extending legal equality to the freed slaves and other blacks. Hatred is an amazingly, grimly persistent thing. As was underlined on February 8 of 1865.

In 1865 the United States finally abolished slavery. It happened far too late and tragically it happened without abolishing bigotry or extending legal equality to the freed slaves and other blacks. Hatred is an amazingly, grimly persistent thing. As was underlined on February 8 of 1865.

Slavery was abolished according to the dictates of the United States Constitution, specifically through the 13th Amendment, passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864 and the House of Representatives on January 31, 1865. Obviously it could not be enforced through the South until the Civil War was officially ended by the Confederate surrender. But it also could not take effect until it was ratified by three quarters of the states following appropriate formal procedures.

Well, sort of. The Union having won the Civil War, it was in a position forcibly to impose governments on the defeated Southern states that did things genuinely elected governments would not do, like ratify the 13th Amendment. (Even, in many states, if those governments resulted from elections in which federal troops forced local whites to let their black neighbours vote.)

Thus Georgia became the crucial 27th state to ratify the Amendment in on December 6, 1865, putting it over the required three-quarters of the 36 states then in the Union including those that had rebelled in 1860-61. The rest subsequently tagged along, though Mississippi unsurprisingly didn’t get to it until March 1995 and "forgot" to send the required notification to the U.S. Archivist for another 18 years until Mississippi resident Ranjan Batra watched the movie Lincoln and started asking awkward questions. But here’s something even worse.

In Delaware, voters rejected the 13th Amendment on February 8, 1865. Yes, rejected it. In Delaware, a state whose inhabitants had voted against secession on January 3, 1861 and supplied 9 infantry regiments to the Union Army. Another Union state, New Jersey, also rejected it in March 1865 but relented in early 1866. But Delaware only ratified it in 1901.

Are you kidding me? Even after the Civil War, which you helped win, you voted to keep slavery? Sadly, it is so.

P.S. Kentucky, formally a Union state but with divided loyalties and dozens of units fighting on both sides in the war, said nay in 1865 and did not repent formally until 1976.

A reminder that "It Happened Today" needs your help. It takes considerable time and effort to produce. So if you're enjoying the feature, make a monthly pledge so I can continue to research and write it.

On February 6 in 1820 something really foolish happened. Which of course does not distinguish it from any other day on the calendar. But this one is a fairly trivial incident in itself that manages at the same time to be a historical whopper.

It is the departure from New York of the Elizabeth, bound for Liberia in West Africa with three white American Colonization Society members and 88 American blacks to solve the whole vexed slavery question by sending freed slaves back to West Africa to establish their own country.

It is hard to overestimate the foolishness of the venture. The fact that all the ACS members and a quarter of the blacks were dead within three weeks from yellow fever while the rest fled back to Sierre Leone to await reinforcements gives you some idea of the early difficulties although to be fair Jamestown was sort of like that too and it worked out eventually.

Liberia never could, in a very fundamental sense. The colony not only survived but prospered, and might have done better still if better-prepared settlers had succeeded in creating a genuine self-governing republic. And if so it might have done considerable good in demonstrating what American slaves could do, and be, once the shackles were struck off.

It failed even at that, as the descendants of the colonists formed a closed elite that subjugated the indigenous population; in rather ghastly typical African fashion it is not even certain when the latter got the vote. So it failed as an example. But Liberia was meant to do more than that.

It was meant to solve America’s slavery problem by exporting it. It was meant to permit emancipation by bigots and among bigots, by promising that once freed the blacks would be sent far away where Americans would not have to put up with them. It was always logistically impossible because there was obviously no way to transport millions of people across the Atlantic with tools and other necessities (there were then nearly 2 million American slaves and 200,000 free blacks) even if they could all have been freed. Dragging them to the New World as naked slaves, with high mortality rates on the dreadful "Middle Passage," was technically feasible if morally repellent. Doing the reverse was morally repellent and technically impossible.

The moral repellence was the worst thing of all. Some ACS members were genuinely unprejudiced but figured that until their countrymen and women had a change of heart the best bet for the freedman or woman was to get to a country not run by whites, as Liberia was not after 1847. Others were benevolent by the standards of the day in rejecting slavery but failed to embrace equality, while a few actually felt colonization was a deft trick for getting rid of troublemaking free blacks to help keep slaves more docile and thus preserve the "peculiar institution".

I know it is easy to say from this distance. But the only proper solution to slavery was to accept that all men are created equal, and to reject both the legal and the social subjugation of any race. If it had been necessary to proceed by abolishing the legal subjugation first and then moving on to the social, I think it would have been an acceptable second best. But nothing good was going to happen as long as people insisted that blacks were inferior and based their solutions on that premise, whether or not those solutions they were as technically absurd as sending them all to West Africa one shipload at a time. Even those genuinely unbigoted ACS members who bowed to their neighbours’ prejudice, though they come out of the story looking a lot better than anyone else, let pragmatism trump principle in ways that ultimately failed badly as they generally do.

Whatever the Liberian colonization experiment did, it utterly failed to solve the problem of American racial slavery that erupted into the internecine Civil War and even once it was done left a poisonous legacy of segregation, injustice and bitterness. As anyone capable of math, let alone moral reasoning, would have known would happen.