“’It is obvious that the mind is moved by incongruity.’ That’s Chesterton writing about laughter. He also said ‘laughter is directly related to the strangeness of man on this strange earth.’ Because we are strangers here, we see the incongruities and they make us laugh.” Eric Scheske in Gilbert! Vol. 7 #5 (March 2004)

Today is the anniversary of King Christian IX of Denmark signing a constitution on November 18, 1863 that got him into The Second Schleswig War with the German Confederation. Which maybe seems like a nasty thing for Germany to do. Or, once I add that this Constitution effectively annexed Schleswig, which the King of Prussia regarded as a violation of the London Protocol, this “Schleswig-Holstein crisis” starts to sound like a Monty Python sketch about European dynastic politics. Except looking back it’s an ominous precursor to both World Wars.

Today is the anniversary of King Christian IX of Denmark signing a constitution on November 18, 1863 that got him into The Second Schleswig War with the German Confederation. Which maybe seems like a nasty thing for Germany to do. Or, once I add that this Constitution effectively annexed Schleswig, which the King of Prussia regarded as a violation of the London Protocol, this “Schleswig-Holstein crisis” starts to sound like a Monty Python sketch about European dynastic politics. Except looking back it’s an ominous precursor to both World Wars.

It is extremely convoluted. There’s a famous remark (well, famous among people who like such things) attributed to British statesman Lord Palmerston that “Only three people have ever really understood the Schleswig-Holstein business—the Prince Consort, who is dead—a German professor, who has gone mad—and I, who have forgotten all about it.” So I’m not going to try to give you all the details lest I go mad or perish. And I’m not really in a position to forget them due to never having known them. But here’s an ominous summary.

Both the First Schleswig War (1848–51) and the Second (1864) were fought over two duchies, Holstein and Lauenburg, driven by secessionist movements by ethnic Germans. And it is worth emphasizing that Denmark had since the 1848 wave of liberal revolutions in Europe been a constitutional monarchy, while Prussia was nothing of the sort and neither was its Austrian ally.

Now you may think it a no-brainer that Prussia and Austria walloped Denmark without undue difficulty and forced it to cede Schleswig, Holstein, and Saxe-Lauenburg. (Yes, another duchy heard from.) And the new King of Denmark did know he was in a tight spot when forced to choose between signing the November Constitution or defying the will of his people. But looking back we are more aware of the looming menace of a unifying German Empire than people might have been in 1864.

Including the Austrians who, um, got into a war with Prussia two years later that lasted only seven weeks and ended in an upset victory for Prussia which thus came to dominate Germany and, after another unexpected victory over France in 1870, to unify most of it under what would not unreasonably be called “Prussian militarism”.

Most. But not all. The ethnic map of Europe is complex even by the normal standards of humanity in which the Wilsonian dream of universal peace due to rigorous avoiding of multiculturalism is impractical. And as Germany continued to swell geographically and in ambition, it used the need to assemble all Germans under a single flag and the alleged mistreatment of German minorities as a pretext to war on one state after another in an fairly unbroken stream from 1864 through 1945. (Also, Prussia/Germany could not build the Kiel Canal to get its battleships back and forth between the Baltic to defeat Russia and the North Atlantic to defeat Britain until it controlled Holstein.)

It looked like Pythonesque rubbish back in 1864. But it would have been better for major powers to stand up to German nastiness back then when it would have been easier to stop.

“The problem [for the Devil, regarding Adam and Eve] was to rid these two of their fantasies, to convince them that the world does exist; that life is not a game but a very serious, even difficult and troublesome thing, and that notions of good and evil are ultimately only relative and impermanent.” Peter Demianovich Ouspensky, Talks With A Devil: Two tales by P.D. Ouspensky

My latest for The Rebel: The audio-only version is available here: [podcast title="Rebel, Nov. 17"]http://www.thejohnrobson.com/podcast/John2016/November/161117Rebel.mp3[/podcast]

On November 17, 1511, England concluded a treaty with Spain, which is pretty unusual given their long history of colonial rivalry and that unpleasant business involving sinking the “invincible Armada” or, to give it its pompously formal and half wildly inaccurate name, “La Grande y Felicísima Armada”. This “Treaty of Westminster” was against France, which is par for the English course. But it does raise the question whether if Henry VIII had not done his theology with a singularly inappropriate body part, his nation’s geopolitical strategy might not have been very different over the next few centuries.

On November 17, 1511, England concluded a treaty with Spain, which is pretty unusual given their long history of colonial rivalry and that unpleasant business involving sinking the “invincible Armada” or, to give it its pompously formal and half wildly inaccurate name, “La Grande y Felicísima Armada”. This “Treaty of Westminster” was against France, which is par for the English course. But it does raise the question whether if Henry VIII had not done his theology with a singularly inappropriate body part, his nation’s geopolitical strategy might not have been very different over the next few centuries.

England was, of course, long determined to prevent a major European power from threatening the “sceptre isle” and its growing overseas possessions. There was a significant division between “blue water” Tories who favoured primary reliance on the Royal Navy to contain the threat, and Whigs who believed it was wiser to intervene in continental affairs rather than wait until one major power became so dominant that it could turn its attention from land to sea. And obviously both strategies were often at the mercy of events. But it wasn’t all chess pieces and geopolitics.

As Daniel Hannan rightly reminds us in Inventing Freedom, the self-understanding of the Anglosphere from the 17th century stressed Protestantism almost as much as liberty. Mind you, in most English-speaking Protestants’ the two were not very separate; an argument could be made not only that Catholicism was associated with absolutism in, say, France but also that it was associated with would-be tyrants in England, especially the Stuarts.

It is this consideration that makes the 1511 alliance with Spain, such as it was, a bit odd, because Spain was another poster child for the allegedly pernicious influence of Catholicism on government and political culture, a major power with an absolutist system and aggressive intentions. It is of course also true that in the twists and turns of European diplomacy alliances were so fluid as to be embarrassing, and England at various times was at war with or allied with Spain and with France, the Netherlands, Russia and anybody else I can name as well as a great many I can’t. And yet on the whole there was a consistent streak of being against Catholic monarchies in the long run and the big picture of British foreign policy.

As I’ve pointed out before, there are two significant theological complications here. First, England was not “Protestant” in anything like the sense that the hard-core Lutheran and Calvinist predestinarians were. Indeed, the English Puritans who had drunk from that particular well were unwelcome in their homeland and contemptuous of the established Anglican church which they regarded, at least while in their doctrinal cups, as little better than the Papacy. In fact I’ve always found Anglican doctrine to be strangely amorphous, partly due to the British genius for compromise; most Anglicans I know are surprised to find that the 39 Articles endorse predestination (while also more or less repudiating it). As Laurence Stern rather neatly put it in the 18th century, “The Anglican Church is the best church, because it interferes neither with a man’s politics nor his religion.” And he was an Anglican clergyman.

The other significant theological complication is that England was itself Catholic from its second evangelization under the Saxons until the break with Rome, and under that faith it developed its remarkable and unique effective culture and system of liberty under law. Magna Carta was the product of a Catholic nation, though one quite unlike the others in many ways, a nation that routinely told the Pope to buzz off (including under King John), and the heroic Archbishop of Canterbury who was the prime mover behind Magna Carta, Stephen Langton, was a Catholic not an Anglican prelate.

These two considerations together suggest that the Anglican Reformation, for all its deplorable excesses, was probably a less significant event than it seemed at least in secular terms. English and then British foreign policy would likely have followed quite a similar course down through the years had Catherine of Aragon born Henry VIII six stout sons, and the English approach to religious doctrine and especially to the relationship between national independence and allegiance to Rome would probably have taken a far healthier course than it often did among the continental powers.

To say so is to suggest the uncomfortable possibility that ideas, especially formal ideas of the sort expressed in catechisms, may have less influence on the minds of men than they sometimes appear to. But then, Paul did say that we see through a glass darkly, a consideration that presumably pertains to rendering unto Caesar as it does to many other things. And in Britain, on that last point, the vision was always less murky than elsewhere, both before and after Henry’s formal break with Rome. Which, again, leads me to suspect that if it hadn’t happened, the strong and effective British opposition to the domination of Europe by any particular type of absolutism, including later both French militant atheism, Napoleonic whatever-that-was-aboutism, the Kaiser’s ostensibly Luthern nationalism and Hitler’s semi-pagan Naziism would have been very similar to what it actually was.

“The mark of the barbarian, as it seems to me, is that he accepts no judgment outside himself. If opinion on his actions is not as he would wish it to be, he appeals to force.” G.K. Chesterton in an interview with The Jewish Chronicle September 22, 1933

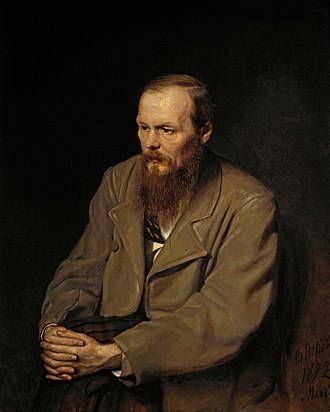

On this date in 1849 the Tsar’s government sentenced Fyodor Dostoevskii to death. It was a true Russian classic.

On this date in 1849 the Tsar’s government sentenced Fyodor Dostoevskii to death. It was a true Russian classic.

In the first place, they arrested and sentenced him for belonging to a revolutionary circle, not for writing unbearably long depressing tormented novels. Not that a man should be sentenced to death for such deeds although if he complains that he’s not enjoying huge commercial success one might justifiably say that the problem might lie with his books at least as much as with his audience.

Nor should he have been sentenced to death for his political views or activities. He held such mad notions as that censorship was bad and so was serfdom. And the “Petrashevsky circle” to which he belonged, partly because they helped him survive despite having no money, was in fact extremely mild in its goals and its, well, I was going to say methods, but really it was just the methods it advocated since it never really got sufficiently organized or energetic to undertake much of anything.

The Tsarist government, painfully aware of the fragility of its superficially omnipotent and seedily magnificent regime, nevertheless reacted harshly to all efforts to develop what we would now call “civil society,” however feeble. So 60 of them were arrested, tried under martial rather than civil law just because, and 15 were sentenced to death, which a higher court stroked its long grey beard and declared to have been a judicial error and they should all be executed. So they were lined up and theatrically pardoned at the last minute by a personal letter from Tsar Nikolai I, who had staged the whole thing.

Instead Dostoevskii and others were, duh, sent to Siberia and treated with such flippant cruelty that it’s amazing anyone survived. But he did, both four years’ hard labour and then even more dangerous compulsory military service, and went on to have a miserable life, sickly, unhappy in love, poor much of the time and a reckless gambler when he had any money.

So now of course he’s a literary giant. But I digress. My point here is that the whole oppression-mock execution affair was a Tsarist classic, witlessly repressive yet unwilling to use genuinely brutal force in a sustained way. The Bolsheviks not only regarded the Tsars as vicious monsters, they somehow convinced the world it was true and that their own regime was, if worse, only marginally so, and at least had better motives.

The truth is that Tsarism was more marked by stagnation than any sort of systematic, energetic effort to make people miserable. The Tsars and their advisors mostly figured that any significant political development would be disastrous and tried to make sure none happened. I don’t endorse this policy, and in the end it failed in a very disastrous way. But I will say this.

If Lenin or Stalin had sentenced a writer to death, or even if they hadn’t, there would have been nothing mock about their execution or mysterious accident. If they sent someone to Siberia, they almost certainly stayed there permanently. And we wouldn’t now have their 38,000-page books to pore over.

“But, as a famous old saying by a great nineteenth-century con man has it, ‘It’s much easier to sell the Brooklyn Bridge than to give it away.’ Nobody trusts you if you offer something for free.” Peter F. Drucker, Managing the Non-Profit Organization: Principles and Practices