In my latest National Post column I argue for marijuana legalization because free adults should make their own choices... and it is not always wrong to get high including on alcohol, nicotine or pot.

In my latest National Post column I explore Bruce Schneier's warning that the Internet of Things is desperately insecure, and suggest that it's strange to run so much risk for so little genuine benefit.

Should someone be excused a serious crime because they flipped out? I’m not referring here to a "not guilty by reason of insanity" plea, which I think virtually everyone concedes is sometimes legitimate. I mean the kind of mental imbalance that hits you suddenly and then recedes leaving you quite sane but also quite free.

Should someone be excused a serious crime because they flipped out? I’m not referring here to a "not guilty by reason of insanity" plea, which I think virtually everyone concedes is sometimes legitimate. I mean the kind of mental imbalance that hits you suddenly and then recedes leaving you quite sane but also quite free.

I ask now because February 19 turns out to be the anniversary in 1859 of the first use of the "temporary insanity" plea in the United States. By a Congressman, no less, one Daniel Edgar Sickles, who had killed a son of the composer of "The Star Spangled Banner". You see, Philip Barton Key II was having an affair with Sickles’ wife and Sickles, whose prior conduct was far from blameless (he married a girl half his age, then consorted openly with prostitutes while she was pregnant), got very annoyed and shot him.

It was a different era. The wealthy and privileged Sickles was apparently so popular that visitors streamed to see him in jail where, among other things, he was allowed to keep a gun. But his high-powered lawyers, including Edward M. Stanton who later served as Lincoln’s Secretary of War, convinced the public and the court that he was so angry at his wife’s infidelity that he was not responsible for what he did in his rage.

It may not have helped the prosecution that newspapers subsequently hailed Sickles for saving women from Key. But still, the case troubles me.

In theory I can see that you could take leave of your senses for various reasons including justified anger in ways that diminish or eliminate legal responsibility. But I’m not convinced I understand the difference between being so angry you shoot your wife’s lover and go to jail (or the gallows) and being so angry you shoot him and it’s OK. As a weird footnote, after making his wife’s cheating a huge public issue Sickles publicly forgave her, which evidently upset people a lot more than the original shooting.

Sickles went on to rise to Major General in the Civil War despite his notorious ambition, drinking and womanizing, eventually commanding III Corps, which he so mishandled at Gettysburg that the resulting action cost him his command (as well as his right leg) though not his commission. He spent years after the war arguing that his blunder had actually been a bold and well-advised strategic stroke and in 1897 he received the Congressional Medal of Honor for it, before ultimately dying in 1914 at age 94.

He was, it seems, a man of remarkably poor judgement in his personal and often public life. But the court ruled that his actual insanity was only temporary and absolved him of murder whereas it sounds to me as though in this case at least it was just a singularly spectacular and consequential display of lifelong lack of self-control.

There are a lot of ways to get into the history books. But here’s one you wouldn’t want. On February 15 of 1933, Giuseppe Zangara tried to assassinate president-elect Franklin Roosevelt. Had he succeeded, it would have been the first time anyone was elected president and then died before taking office.

There are a lot of ways to get into the history books. But here’s one you wouldn’t want. On February 15 of 1933, Giuseppe Zangara tried to assassinate president-elect Franklin Roosevelt. Had he succeeded, it would have been the first time anyone was elected president and then died before taking office.

It didn’t happen then, and it hasn’t happened since, something I refrain from mentioning between any election and inauguration lest I should be suspected of trying to jinx the president-elect. As a matter of fact, no one has ever died between being nominated by a major party and the election either. Leaving aside violence, you’d think simply by the odds it would have happened to somebody. (Democratic lion Stephen A. Douglas, one of Lincoln’s opponents in the 4-way 1860 election, did die suddenly less than three months after his victorious rival was inaugurated.)

As for getting into the history books anyway, a dismal footnote to Zangara’s failed attempt is that in the process, standing on a wobbly folding chair and fighting a crowd trying to subdue him, he managed to shoot four other people including Chicago mayor Anton Cermak, who died of his wounds on March 6, two days after Roosevelt’s inauguration. So Cermak becomes "Who was that guy shot by mistake next to FDR?"

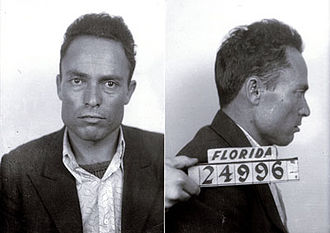

Meanwhile Zangara was executed in "Old Sparky," the Florida State Prison’s electric chair, on March 20, justice being swifter in those days. (For what it’s worth, the judge who sentenced him to death called for a complete handgun ban.) And in the process Zangara did make a sort of history.

You see, the rules said prisoners could not share a cell prior to execution but as someone else was awaiting capital punishment he obliged them to expand the "death cell" into the now proverbial "Death Row". It’s not exactly what you put down as your ambition in your high school yearbook. But it beats being the guy assassinated by mistake while the real target wasn’t becoming the first ever president-elect not to make it to Inauguration Day.

Apparently February 4 is a day to be proud of in Japan because 46 guys killed themselves as a reward for a good deed. I have to say it’s not my idea of a red-letter day.

Apparently February 4 is a day to be proud of in Japan because 46 guys killed themselves as a reward for a good deed. I have to say it’s not my idea of a red-letter day.

The story is that in 1703 in what is now Tokyo and was then Edo, all but one of the "Forty-seven Ronin" committed seppuku not because they had failed to avenge their master’s death but because they had succeeded. The "Akō incident" became a "national legend" in Japan, even the national legend, a shining example of the samurai code of honour. And yes, I do have to explain it if you’re not Japanese. Or rather describe it. I do not think it can be explained in the sense of being defended.

We’re not sure the details as it was not written up in reliable detail for nearly a hundred years thanks to censorship laws. But the basic story is as follows: These samurai were left leaderless, or "ronin," after their lord Asano Naganori was forced to kill himself for attacking a wretched court official named Kira Yoshinaka. So the ronin spent a year working out a plot to kill Kira, after which they had to kill themselves because of the shame of committing murder.

As you already sense, I find the whole thing unspeakably weird. It begins with the key fact that Kira was abusive and corrupt. Two hapless local officials, Lord Kamei and Asano himself, were ordered to prepare a reception for the Emperor’s envoys and were given etiquette lessons by Kira. But they didn’t give him sufficient bribes so he abused them so badly that while Asano kept his cool Kamei lost his and was going to do Kira in.

To save Kamei’s life, his own advisors quickly hustled up a major bribe for Kira who then began treating their master better. But he kept taunting Asano and when he ridiculed him as an ill-mannered rustic, Asano snapped and went after him with a dagger, giving him a minor scratch on his face. (Not exactly what one would hope from a samurai, I note in passing; I thought these guys could kill you with a greeting card.)

Despite the feeble nature of the attack, the very fact of drawing a weapon within Edo Castle was fatal and Asano had to kill himself, his family lost his possessions and lands, and his followers were made outcasts. And so everybody went along with it because I mean what’s blatant injustice when honor is involved or something.

Except there was this group of 47 who took a secret oath to get revenge even though they’d been ordered not to. They went underground as traders, laborers or drunken debauchees. And after several years they managed to infiltrate and storm Kira’s home, overcome his retainers abetted by the silence of his neighbours who all hated him, caught him and respectfully besought him to kill himself like a true samurai.

He chickened out, wuk wuk, betrayer of the code, so the ringleader sawed off his head with a dagger. Then the ronin carefully extinguished all lamps and fires so the neighbours’ houses were not in danger from a general conflagration, and left with the head.

One of the ronin was either sent to report the success of their mission to Asano’s old domain of Akō or else ran away. Either way he apparently came back much later, was pardoned, and lived to a ripe old age before being buried with the others. The rest went to the temple where their master was buried, washed the head carefully, then put it and the dagger on his grave, offered prayers, left the abbot money for their own funerals, and turned themselves in.

The situation was awkward for the shogun, given general approval of their deed plus its fairly obvious justification under almost any meaningful moral code. So he couldn’t just execute them. Instead he ordered them to execute themselves and they did.

So popular is this tale in Japan that the temple where the ronin’s remains are interred holds a festival every December 14, the successful attack having occurred on the 14th day of the 12th month in the old Japanese calendar. But it was on the 4th day of the 2nd month that they all cut out their guts and had a second behead them, the final and apparently crowning act of the drama. And one I flatly admit I cannot sympathize with or support.

Were the ronin right or wrong to kill Kira? And if they were right, why celebrate their being put to death for it? Surely they should have gone down fighting. It is simply not possible to imagine the surviving Magnificent Seven ending the film by simultaneously raising their revolvers to their heads and blowing their brains out in unison and making the classic American film in the process.

"The 47 Ronin" a beautiful and picturesque story, to be sure. And apparently Asano’s brother did get his title and a bit of his land back. But it’s also very disturbing. And not least because ordering them to commit suicide, when they apparently had or felt they had no choice, is not an alternative to executing them. It’s just a hypocritical fiction, a way for the shogun to be, as Orwell put it, somewhere else when the trigger is pulled.

Even more baffling to me, in a moral sense, is the lack of concern with right and wrong, indeed the failure to see them as necessarily separate and opposite qualities. The whole story seems to hinge on the ronin’s actions being simultaneously both right and wrong.

I think they were just right. The guy who taunted their lord was no paragon of virtue attacked by mistake. He was a crooked wretch who deserved to be horsewhipped on the steps of his club or gunned down by John Wayne in a classic Western quick-draw showdown. And there’s no suggestion in the story of a kind of Shakespearean scenario in which Asano had a better course of action. Kamei’s men you recall had simply bribed Kira. The emperor or shogun was not, one feels, likely to render justice.

So where’s the vindication of right conduct? Instead there’s something fatalistic, even fey, about a group of such dedicated men bent on making a ritually beautiful bad end for doing a good deed.

To me this story makes no sense. If a particular act of revenge is wrong, don’t do it. And don’t later celebrate those who did. But if it is right, stand by it. There is a weird excluded middle here, where an act is simultaneously right and wrong and ritual rather than moral judgement determines action.

It is not a direct line from the "Akō incident" to Pearl Harbor. But the two are connected by a peculiar, ornate, gorgeously perverse refusal to put individual conscience ahead of "the code", a determination to reject principle on principle.

In my latest National Post column, I say the mass murder in a Quebec mosque should remind us to seek compassion in our hearts and a civil tone in public debate on difficult issues.

On January 31 of 1801, lame-duck U.S. President John Adams appointed John Marshall Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Such appointments often backfire; Eisenhower would later bitterly regret elevating Earl Warren to Marshall’s old job. And at the time it was largely seen through the partisan lens of Adams’ effort to stack the judiciary against his hated rival Thomas Jefferson. But it turned out to be one of the greatest appointments in American history.

On January 31 of 1801, lame-duck U.S. President John Adams appointed John Marshall Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Such appointments often backfire; Eisenhower would later bitterly regret elevating Earl Warren to Marshall’s old job. And at the time it was largely seen through the partisan lens of Adams’ effort to stack the judiciary against his hated rival Thomas Jefferson. But it turned out to be one of the greatest appointments in American history.

Adams had originally offered the job to another leading member of what was fast becoming the Federalist party, John Jay. But Jay turned it down partly on the grounds that the Supreme Court had insufficient "energy, weight, and dignity." Which might sound like a weird thing to say given the importance of the judiciary in the American system of checks and balances. But it was in fact not clear in 1801 that the Court was an equal branch or that it could, in fact, invalidate statutes as unconstitutional.

It was Marshall himself, whose skilful and congenial guidance included changing the practice of each judge issuing his own opinion to the presentation of a majority or even unanimous consensus, who made the Court what it has been since. And the critical turning point was Marbury v Madison in 1803 in which a unanimous Court struck down portions of the Judiciary Act of 1789 as unconstitutional.

It was, interestingly, the only time in his 35 years as Chief Justice that the Marshall Court declared an Act of Congress unconstitutional. And it was one whose practical impact pleased the incumbent President and Congress even though they were Jeffersonian Republican foes of the Federalist Party, which probably helped it avoid becoming a focus for partisan wrangling. But however that may be, it was a crucial step in the evolution of the American system to the point that one prominent constitutional scholar declared that only when Marshall finished reading the court’s opinion in Marbury v Madison was the Grand Convention that wrote the Constitutional entirely adjourned.

As for John Adams, who spent a long and productive life in service of his country, he later said "My gift of John Marshall to the people of the United States was the proudest act of my life." It may also have been his most effective.

In my latest National Post column I denounce the legal Juggernaut that has rolled over a blameless Ontario couple and increasingly menaces us all. (My bad: In the piece I misnamed the outrageous Ontario law in question; its actual Orwellian title is the Civil Relief Act.)