Here’s one I do like. On February 27, 1782, the British House of Commons voted to throw in the towel in the American Revolutionary War.

Here’s one I do like. On February 27, 1782, the British House of Commons voted to throw in the towel in the American Revolutionary War.

I like it partly because my sympathies are very much with the revolutionaries seeking to uphold their ancient British liberties, not with the King and his ministers trying to suppress them. And I like it partly because I can think of few greater affirmations of those liberties that, in such a difficult and embarrassing situation, it was the representatives of the British people who took the king by his frilly collar and said "Stop!" Once again, Parliament checked an expensive, oppressive hare-brained executive branch scheme which was, in large measure, the point of the British constitution essentially from Magna Carta onward.

This vote was no formality. Far from it. The King remained an important player in the British system even when he was obviously messing up badly. And despite the highly unfavourable state of the military effort in what had recently been the 13 Colonies after the crushing British defeat at Yorktown by a combined American-French force, the February 27 1782 vote was close, 234 to 215. And that narrow 19-vote margin was very important.

It set in motion a highly favourable chain of events leading to quick reconciliation between the former belligerents. Including that the American peace commissioners, the exalted trio of Benjamin Franklin, John Adams and John Jay, proceeded to make a separate peace with Britain despite pledges to France, which had swooped on her old foe, not to do so.

Within an amazingly short period, and despite the stupid War of 1812, Britain and the United States were tacit allies in maintaining world order, an arrangement that persisted from the 1824 Monroe Doctrine with some bumps and bruises right down to their formal alliance in 1917. And while it took statesmanship to bring it about and maintain it, the structural basis was their shared devotion to liberty under law and to popular sovereignty. With, of course, the usual qualifications about unjust exclusion of some groups from the blessings of liberty, most spectacularly in the United States black slaves and then ex-slaves.

In the Capitol Rotunda in Washington there is a gold replica of Magna Carta that we were kindly permitted to film in 2015, given by the British Parliament in 1976 in powerful acknowledgement that two centuries earlier the greatest devotees of traditional freedom and the rights of the people had been on the west side of the Atlantic. But they were still strongly represented in Britain including in Parliament on that important date.

Liberty is often under siege. But where the roots are deep, it has enormous strength and manages to flourish despite and sometimes even during storms. Including Parliament yanking George III back to his so-called senses on behalf of ordinary Britons on February 27, 1782.

On February 25 of 1870 Hiram Revels became the first black member of the United States Congress as, of all things, a Republican Senator from Mississippi. It was a great achievement, and also a dead end.

On February 25 of 1870 Hiram Revels became the first black member of the United States Congress as, of all things, a Republican Senator from Mississippi. It was a great achievement, and also a dead end.

Revels himself thoroughly deserved to be a Senator, in a positive sense. As an individual, he was not merely intelligent but wise, principled and reasonable, and an advocate of generosity in putting the Civil War behind Americans. And as a member of a long-oppressed race, he belonged in the Senate as part of a long-overdue extension of full citizenship to blacks including unfettered participation in the political community.

Nor is the problem that he was not democratically elected. Mississippi was at the time occupied by federal troops, who dictated election results dramatically at odds with the wishes of the locals. Or rather, the white locals. Mississippi was a die-hard white supremacist pro-Confederate state in a region where it was hard to stand out in that regard. And it is problematic to say that it is justified in dictating election results by force because the majority is wrong on an important issue, even a vital moral one. But whites were not a majority in Mississippi in those days.

In fact Mississippi was a majority black state from well before the Civil War into the 1930s. So the result of full, fair, free adult suffrage would have been the election of large numbers of blacks at every level, and the indignant rejection of segregation and race hate. That a bitter white minority would control Mississippi politics in the absence of armed outsiders was horribly unjust and federal troops were right to intervene even if the result was not precisely what would have happened in a genuinely free and fair election in which blacks were neither disenfranchised outright or terrorized into not voting.

So here’s the problem. Slavery had such a negative impact on the literacy, prosperity and social organization of blacks in Mississippi that in the absence of external force they were not going to prevail at the polls or anywhere else despite being a majority until the hearts of whites were changed. And the federal government, and voters in the American north, were not prepared to continue policing Mississippi elections until that happened. By 1877, following the corrupt bargain that secured Rutherford B. Hayes a single term as president by falsifying election results in three southern states, the North pulled out and left southern blacks at the mercy of their white neighbours.

Given this reality, the result of a punitive, in-your-face Reconstruction was further to entrench race hatred and make anything vaguely resembling an open mind on the subject seem treasonous to those who, once federal troops left, would be in charge for the foreseeable future. And that is what happened.

Revels himself warned against this approach, including a very pointed letter to President Ulysses S. Grant in 1875, after he had left the Senate to become the first president of Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College. In that letter he exaggerated the willingness of white Mississippians to let go of "the bitterness and hate created by the late civil strife". But he did warn that punitive Reconstruction was calculated to keep it alive.

What, then, should have been done? No conceivable Reconstruction policy would have brought a quick end to bigotry in white hearts or key political institutions of Mississippi and its neighbours, not even a generous one. Under the actual circumstances, there was a long legal battle against seating Revels in the Senate based on all sorts of arguments including that the awful 1857 Dred Scott Supreme Court decision meant he was not a citizen before ratification of the 14th Amendment in 1868 and thus did not meet the nine-year-citizenship requirement.

Republicans answered with all sorts of arguments of their own, from the narrowly legal to hey we won the war. And by straight party vote, Revels was seated. It seems the right thing to do even knowing the sorry long-term outcome. And I greatly admire Revels himself for speaking so wisely about reconciliation. But he was seated at gunpoint and as soon as white voters in Mississippi and other southern states were left to their own devices, they were able to oust blacks from Congress and local legislatures using the same device and did so.

So what would you have done? Not to seat Hiram Revels and his various black colleagues in Southern legislatures in the 1870s would have been to be complicit in injustice. But to seat them, deepening white bitterness, and then leave, did neither southern blacks nor southern whites any good.

Clearly the only solution was to stay until hearts were changed. But that solution is deeply ahistorical. In fact between 1901 and 1929 there was not a single black in Congress. And I don’t just mean in the South. (They began to be reelected in the New Deal, and this time as Democrats from northern cities.)

There’s the core of the problem. Northerners may have disliked, even despised, slavery and then former slave-owners. But they did not love the slaves or ex-slaves. They did not put blacks into southern legislatures to help blacks but to hurt whites. And it ended up hurting everyone.

So if you’d been there in 1870, with modern attitudes, the only policy you could conceivably have supported without reservation would have been for northerners to insist on genuine protection of civil rights in the south. Not just for a season to annoy defeated Confederates but for as long as it took out of genuine commitment to equality for blacks and compassion for the closed minds of most white southerners. And there’s no way you could have found anything like sufficient support for this plan.

It is because of dilemmas like this one that I am convinced that, in our own day, we should take what we can get when it seems to constitute genuine progress toward a worthy goal. But we should never be afraid to speak up, charitably if we can manage it, in defence of radical goals when all so-called practical, prudent and moderate courses point clearly toward dishonourable disaster. As they surprisingly often do, and did in 1870 in the American South.

To say that we cannot undo history is not to say that we should not recall genuine injustices. For instance the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, signed on September 27, 1830 but proclaimed on February 24, 1831. The first "removal treaty" under the Jackson-era Indian Removal Act, between the Choctaw and the United States Government, it traded some 11 million acres of fertile land in what is now Mississippi for 15 million acres of barren scrub in Oklahoma. Or else.

To say that we cannot undo history is not to say that we should not recall genuine injustices. For instance the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, signed on September 27, 1830 but proclaimed on February 24, 1831. The first "removal treaty" under the Jackson-era Indian Removal Act, between the Choctaw and the United States Government, it traded some 11 million acres of fertile land in what is now Mississippi for 15 million acres of barren scrub in Oklahoma. Or else.

Now the Treaty did give those Choctaw who chose to remain in Mississippi U.S. citizenship, the first significant non-European group to receive it. And that is a path that should have been taken far more, and with far better goodwill on the part of citizens and governments in the United States and Canada. But it would also have been essential to leave the Choctaw, as citizens, in possession in fee simple of the land they had once held traditionally. And that was not something the American government was willing to do. Instead, each Choctaw who remained where he or she was got one "section" of 640 acres, plus a half section for older and a quarter for younger children. The rest of the land was, well, stolen.

The Choctaw were the first of the "Five Civilized Tribes" to be subjected to this unfair process and sent along the "Trail of Tears" to Oklahoma where, of course, the land was not of equivalent quality in any case. (The other four were the Creek, Cherokee, Chickasaw, and Seminole.) Around 15,000 of them went to Oklahoma, which is actually a Choctaw word (it means "red people"). And there the Choctaw were promised in the treaty "Autonomy of the Choctaw Nation (in Oklahoma) and descendants to be secured from laws of U.S. states and territories forever" which of course did not happen either. As to the roughly five to six thousand who stayed, they were harassed, abused, and encouraged to move to Oklahoma into the early 20th century.

I believe the rise of the United States to superpower status militarily, economically and culturally has been an enormous boon to the world and to Canada. But there were aspects of it, from slavery to foreign policy misdeeds to the "Indian removal policy", that remain wrong even as part of a story that turned out very well.

One Choctaw chief, George W. Harkins, wrote a letter to the American people that included the poignant phrase "Much as the state of Mississippi has wronged us, I cannot find in my heart any other sentiment than an ardent wish for her prosperity and happiness." I share his sentiment. But surely one should also wish that for the descendants of those who were dispossessed.

Not by restoring conditions of life as they had been in 1830 or 1430, but by compensation to individuals for wrongs to their direct ancestors that can reasonably be demonstrated in court, full citizenship without social prejudice, and frank recognition of the historical wrong as an outrage not only to those directly affected, but to all decent people.

Should someone be excused a serious crime because they flipped out? I’m not referring here to a "not guilty by reason of insanity" plea, which I think virtually everyone concedes is sometimes legitimate. I mean the kind of mental imbalance that hits you suddenly and then recedes leaving you quite sane but also quite free.

Should someone be excused a serious crime because they flipped out? I’m not referring here to a "not guilty by reason of insanity" plea, which I think virtually everyone concedes is sometimes legitimate. I mean the kind of mental imbalance that hits you suddenly and then recedes leaving you quite sane but also quite free.

I ask now because February 19 turns out to be the anniversary in 1859 of the first use of the "temporary insanity" plea in the United States. By a Congressman, no less, one Daniel Edgar Sickles, who had killed a son of the composer of "The Star Spangled Banner". You see, Philip Barton Key II was having an affair with Sickles’ wife and Sickles, whose prior conduct was far from blameless (he married a girl half his age, then consorted openly with prostitutes while she was pregnant), got very annoyed and shot him.

It was a different era. The wealthy and privileged Sickles was apparently so popular that visitors streamed to see him in jail where, among other things, he was allowed to keep a gun. But his high-powered lawyers, including Edward M. Stanton who later served as Lincoln’s Secretary of War, convinced the public and the court that he was so angry at his wife’s infidelity that he was not responsible for what he did in his rage.

It may not have helped the prosecution that newspapers subsequently hailed Sickles for saving women from Key. But still, the case troubles me.

In theory I can see that you could take leave of your senses for various reasons including justified anger in ways that diminish or eliminate legal responsibility. But I’m not convinced I understand the difference between being so angry you shoot your wife’s lover and go to jail (or the gallows) and being so angry you shoot him and it’s OK. As a weird footnote, after making his wife’s cheating a huge public issue Sickles publicly forgave her, which evidently upset people a lot more than the original shooting.

Sickles went on to rise to Major General in the Civil War despite his notorious ambition, drinking and womanizing, eventually commanding III Corps, which he so mishandled at Gettysburg that the resulting action cost him his command (as well as his right leg) though not his commission. He spent years after the war arguing that his blunder had actually been a bold and well-advised strategic stroke and in 1897 he received the Congressional Medal of Honor for it, before ultimately dying in 1914 at age 94.

He was, it seems, a man of remarkably poor judgement in his personal and often public life. But the court ruled that his actual insanity was only temporary and absolved him of murder whereas it sounds to me as though in this case at least it was just a singularly spectacular and consequential display of lifelong lack of self-control.

Vermont is not all that controversial. Is it? No. It’s just this rather pleasant New England state with the odd distinction of being among the most Democratic in the United States and the most heavily armed. But precisely because it does not arouse strong passions, it’s interesting to reflect on its admission to the Union on February 18 of 1791.

Vermont is not all that controversial. Is it? No. It’s just this rather pleasant New England state with the odd distinction of being among the most Democratic in the United States and the most heavily armed. But precisely because it does not arouse strong passions, it’s interesting to reflect on its admission to the Union on February 18 of 1791.

Interestingly, that decision was controversial, because Vermont was on land ceded by the French after the Seven Years’ War and at one point New York, Massachusetts and New Hampshire all claimed some of it. By 1770 it was basically New York versus the local staid pious New England rowdies, especially Ethan Allan and his "Green Mountain Boys" who were frankly rather scary vigilantes against New York authority.

Until, of course, the British decided to suppress liberty in their colonies at which point everybody decided to forget their old quarrels and go get George III even though Ethan Allan continued to contest New York’s authority. So here’s the interesting thing.

In the general uprising against British authority, a group of Vermonters gathered in convention declared themselves a sovereign state in 1777. Then they named themselves Vermont, and adopted the first constitution in North America to ban adult slavery. (Eighty-one years later, in 1858, Vermont banned slavery altogether.)

For fourteen years people tried to avoid the awkward topic of whether there was or was not a "Vermont" even though it issued its own money, had a postal service and elected governors. And Congress could not act without New York’s consent under Article IV, Section 3 of the constitution. Finally New York threw in the towel and, after successful negotiations over where exactly the border lay and what compensation was due to New Yorkers whose land titles had been ignored in Vermont, Vermont became the 14th state and (duh) the first new one after the original 13.

What’s interesting here is that Vermont’s claim to statehood rested on two key points. First, the people who then lived there wanted it. And second, they had successfully acted as a state in fact. In short, people bowed to reality.

I’m not saying might makes right. The origins of many nations and subnational jurisdictions give serious pause on grounds of legitimacy, especially in a world that no longer recognises the "Doctrine of Discovery" of places that already had people in them, and is distinctly uneasy with the "Doctrine of Conquest". But the simple fact is that as far back as you can find anything resembling reliable records, land is in possession of those who took it from others including the aboriginals who were in Vermont when Europeans showed up. And sometimes de facto is the best basis you can find for de jure, that is, you agree that Vermont should be accepted as existing essentially because it does exist.

We still hope for perfect justice. We cannot do less. But at times we admit that things are what they are and we must make the best of them.

I do not think a great many people, even in New York, go about today saying Vermont is a fraud and an imposition. But precisely because it does not arouse strong passions, it’s a good test case of our willingness to defy, or accept, what actually does exist in favour of what we wish existed or feel might perhaps have existed under other circumstances.

There are a lot of ways to get into the history books. But here’s one you wouldn’t want. On February 15 of 1933, Giuseppe Zangara tried to assassinate president-elect Franklin Roosevelt. Had he succeeded, it would have been the first time anyone was elected president and then died before taking office.

There are a lot of ways to get into the history books. But here’s one you wouldn’t want. On February 15 of 1933, Giuseppe Zangara tried to assassinate president-elect Franklin Roosevelt. Had he succeeded, it would have been the first time anyone was elected president and then died before taking office.

It didn’t happen then, and it hasn’t happened since, something I refrain from mentioning between any election and inauguration lest I should be suspected of trying to jinx the president-elect. As a matter of fact, no one has ever died between being nominated by a major party and the election either. Leaving aside violence, you’d think simply by the odds it would have happened to somebody. (Democratic lion Stephen A. Douglas, one of Lincoln’s opponents in the 4-way 1860 election, did die suddenly less than three months after his victorious rival was inaugurated.)

As for getting into the history books anyway, a dismal footnote to Zangara’s failed attempt is that in the process, standing on a wobbly folding chair and fighting a crowd trying to subdue him, he managed to shoot four other people including Chicago mayor Anton Cermak, who died of his wounds on March 6, two days after Roosevelt’s inauguration. So Cermak becomes "Who was that guy shot by mistake next to FDR?"

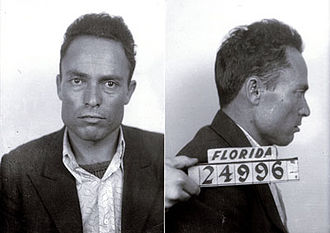

Meanwhile Zangara was executed in "Old Sparky," the Florida State Prison’s electric chair, on March 20, justice being swifter in those days. (For what it’s worth, the judge who sentenced him to death called for a complete handgun ban.) And in the process Zangara did make a sort of history.

You see, the rules said prisoners could not share a cell prior to execution but as someone else was awaiting capital punishment he obliged them to expand the "death cell" into the now proverbial "Death Row". It’s not exactly what you put down as your ambition in your high school yearbook. But it beats being the guy assassinated by mistake while the real target wasn’t becoming the first ever president-elect not to make it to Inauguration Day.