“Go not for every grief to the physician, nor for every quarrel to the lawyer, nor for every thirst to the pot.” George Herbert

But “It Happened Today” needs a break. So it won’t be appearing for a while. Thanks for reading, and stay tuned.

“He had made his wish and the wish had not only been granted, it had been stuffed down his throat.” Ian Fleming, Goldfinger

Here’s a cool thing about the founding of the United States. The social contract.

Here’s a cool thing about the founding of the United States. The social contract.

You know, that fiction by which political philosophers like John Locke explore the fundamental question of why and how we form societies with governments, and what powers the state does or does not possess based on the purpose and process by which we create them. I’m all for this sort of analysis, especially when it is John Locke doing it. But it’s just an imaginative way of thinking about the problem, people having formed themselves into societies long before there was writing or political science. There is no “social contract” signed by Neanderthals or somebody using red ochre on a buffalo hide unearthed in a cave in southern France.

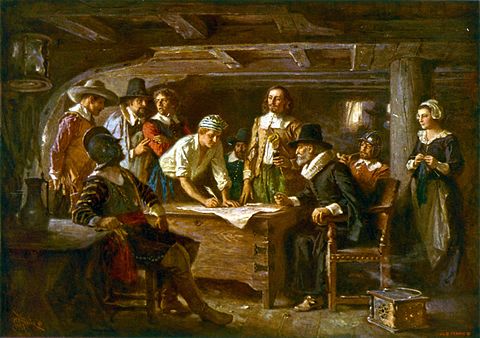

Unless, of course, you’re the Pilgrims. These early migrants to what later became Massachusetts were an obscure sect within Puritanism with limited actual impact on the colony and later the nation. But when they were about to disembark from the Mayflower, on November 21 1620 (on the old calendar November 11) they signed the following document:

“In the Name of God, Amen./ We whose names are underwritten, the loyal subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord, King James, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France and Ireland King, Defender of the Faith, etc./ Having undertaken, for the Glory of God, and advancement of the Christian Faith and Honour of our King and Country, a Voyage to plant the First Colony in the Northern Parts of Virginia, do by these presents solemnly and mutually in the presence of God, and one of another, Covenant and Combine ourselves together into a Civil Body Politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact, constitute and frame such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions and Offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the Colony: unto which we promise all due submission and obedience. In witness whereof we have hereunder subscribed our names at Cape Cod the 11 of November, in the year of the reign of our Sovereign Lord, King James of England, France and Ireland the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth Ano. Dom. 1620.”

The Pilgrims are the only people I know who actually did this. On the eve of building a new society physically, that a disparate group from various parts of England that were currently the frequently very sea-sick inhabitants of a ship (the crew dubbed them “puke-stockings” which pretty much says it all including that some slang words are very durable) made a written covenant that created the body politic and they didn’t get it from the king. They did it themselves. The Mayflower Compact bowed down to James I but didn’t actually ask his permission. And they pledged allegiance to the covenant not the king.

In some sense all Constitution-making, if done through popular approval, has this quality. But that sort of Constitution-making is a modern habit and it all traces back to the Pilgrims. And before they more or less vanished into history, despite their place in folklore, and despite the misuse of the power to make new Constitutions in places like Revolutionary France or the U.S.S.R. they gave us a great gift by showing us the people actually constituting themselves and asserting their right to make, control and if necessary abolish governments that arise through the consent of the people when they make the very real social contract.

It’s about this whale. Specifically the apparently obscure fact, even by the standards of this series, that on November 20, 1820, an 80-ton sperm whale attacked and sank the Massachusetts whaling ship Essex off the western coast of South America. You go whale, you may be thinking. Instead it was you go Herman Melville, which isn’t as good.

It’s about this whale. Specifically the apparently obscure fact, even by the standards of this series, that on November 20, 1820, an 80-ton sperm whale attacked and sank the Massachusetts whaling ship Essex off the western coast of South America. You go whale, you may be thinking. Instead it was you go Herman Melville, which isn’t as good.

It was also you go cannibalism, because the Essex sank 2,000 miles off the coast. And during 95 harrowing days at sea the originally 20 survivors ate five of their fellows who died and then, yes, began drawing lots to see who else they would eat and got through seven others before the last eight were rescued.

Two of that eight later wrote accounts of their suffering that, according to Wikipedia, “inspired Herman Melville to write his famous 1851 novel Moby-Dick.” Which is a bit odd because unless I missed something, nobody eats anybody in Moby Dick.

You have read it, of course. I mean, it’s the Great American Novel or at least one of them, along with The Great Gatsby, The Grapes of Wrath and some dreck by Hemingway all of which make you wonder what’s so great about great American novels. I personally found Moby Dick ponderous, and the endless intercalary chapters about whale skin were a total waste of paper and I would say my powers of concentration had I in fact bothered to concentrate on them sufficiently to be entirely sure they were intercalary chapters and not just long boring asides.

Which I think I just engaged in one of here. My point is, you have very probably been forced to read Moby Dick at some point, in which case you may very well share my view that the best description of it ever is in the musical Wonderful Town where a woman is trying somehow to jump-start the conversation at a failing cocktail party and comes up with “I was re-reading Moby Dick the other day... I haven’t read that since… well... I'm sure none of us has. It's worth picking up again...:” and then into the ensuing deadly silence petering out with “it's about this... whale.”

Apparently it’s not. It has a whale in it, a big one, white, bites off legs and stuff, modeled on a real, elusive albino whale called Mocha Dick. But apparently it’s really about all those great things like God, social divisions, good and evil and how to render blubber. Not that anyone noticed in 1851 when it was published; it was a commercial failure that sold barely 3,000 copies during Melville’s lifetime and was out of print when he died in 1891. But then people like Faulkner and D.H. Lawrence decided it was strange and wonderful. And to be sure the opening line “Call me Ishmael” is so famous even I have parodied it.

To be fair, there is one thing in the book I do remember approvingly: Melville’s description of the incredible perils of manning a small whaling-boat trying to harpoon a whale, with the threat of death ever-present from the whale’s tail, a rope snaring your arm or leg as it hisses out affixed to a harpoon that has struck its target and so on. And then his point that we do not feel any such danger on an apparently safe city street yet death may await as at any turn from a runaway horse (it was 1851), a falling brick or some such accident. Oh, and the incredibly gross bit where someone harpoons an elderly whale in a giant blood blister. That has stayed with me.

For the rest, it’s one of those classics that makes we wonder about the canon. Though perhaps I should reread it. I haven’t since… well, I’m sure none of us have. But it’s about this whale and, given what humans have done to whales in recent centuries, I do like the bit where he sinks the ship.

P.S. It also set up the gag in the dud sequel Son of the Pink Panther where it turns out Clouseau and Marie Gambrelli had a son who is now a policeman and doesn’t know who his father was because, she explains “Imagine you've always wanted to be a great fisherman... and suddenly you discover that your father was Captain Ahab.”

“We talk much about ‘respecting’ this or that person’s religion; but the way to respect a religion is to treat it as a religion: to ask what are its tenets and what are their consequences. But modern tolerance is dearer than intolerance. The old religious authorities, at least, defined a heresy before they condemned it, and read a book before they burned it. But we are always saying to a Mormon or a Moslem, ‘never mind about your religion, come to my arms.’ To which he naturally replies, ‘But I do mind about my religion, and I should advise you to mind your eye.’” G.K. Chesterton in Illustrated London News May 13, 1911, quoted in Gilbert Magazine Vol. 15 #8 (July-August 2012)

The audio-only version is available here: [podcast title="Ask the Professor, November 19"]http://www.thejohnrobson.com/podcast/John2016/November/Ask_Professor_63.mp3[/podcast]

Then there’s Bulgarian victory in the Battle of Slivnitsa. When, you cry, is there Bulgarian victory in the Battle of Slivnitsa, and against whom? Why, on November 19, 1885, in the Serbo-Bulgarian War, which helped solidify the unity of the Principality of Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia.

Then there’s Bulgarian victory in the Battle of Slivnitsa. When, you cry, is there Bulgarian victory in the Battle of Slivnitsa, and against whom? Why, on November 19, 1885, in the Serbo-Bulgarian War, which helped solidify the unity of the Principality of Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia.

OK, you’re thinking. Another Monty Python sketch. But nay. It was in fact a surprising victory for Bulgaria’s young army, dubbed by some the “Battle of the captains vs the generals”. And as for the feeling that even if you knew where Rumelia was you would not care, not even if it was a semi-autonomous region of Ottoman Empire with a Christian governor following the end of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78 and the Congress of Berlin in 1878 (no, I’m not making it up and no, I won’t shut up), remember that the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire helped trigger World War I as the Great Powers scrambled to absorb its Balkan fragments or prevent others from doing so.

The Principality of Bulgaria was itself another bit of the Ottoman Empire, made entirely autonomous in 1878. But there was no taping the crumbling corpse of the Ottoman Empire in the late 19th century, and so something constructive had to be done. Instead the usual squabbling ensued.

For some reason Russia and Bulgaria had a falling out in 1883 and so the Russians didn’t want Bulgaria to absorb Rumelia, which is why they withdrew all their officers leaving the Bulgarians without so much as a major, let alone a general. But the Bulgarians were bent on reunification and their prince had no choice but to go along or be deposed.

So they went to war, and while the Ottomans sat there shedding bits, the Serbians intervened. And while there’s an undeniable comic opera feel to these understrength, underarmed and undercommanded Bulgarian battalions and Eastern Rumelian militia with one bad railway upsetting the confident Serbs, only to be stopped by Austrian intervention after which Bulgaria was unified in 1886 but Prince Alexander was deposed by Russian-sympathizing officers the same year (stop here for deep breath), the complex mix of Catholic versus Orthodox and Slav versus Germans and others, as well as divisions among Slavs, exacerbated by growing nationalism, was a proverbial powder keg to the point that the punchline of a popular 1913 London music hall song was “There’ll be trouble in the Balkans in the spring.” And the next summer trouble in the Balkans plunged Europe and the world into the First World War.

I’m not saying I would have known what to do about the Battle of Slivnitsa even if I could have pronounced it, found it on a map without Google, and intervened from London or Paris in 1885. But it’s yet another warning that comic opera clashes in places with funny names are often harbingers of things that are not remotely funny.