An event on January 20, by contrast with much of the rubbish cluttering up the pages of history, was no mere incident. On this date Simon de Montfort, leader of a baronial revolt against the hapless profligate King Henry III of England, summoned a parliament to legitimize his claim to control England. And to strengthen his position against his fellow barons as well as that of the rebels generally, he brought in the common people as full participants.

An event on January 20, by contrast with much of the rubbish cluttering up the pages of history, was no mere incident. On this date Simon de Montfort, leader of a baronial revolt against the hapless profligate King Henry III of England, summoned a parliament to legitimize his claim to control England. And to strengthen his position against his fellow barons as well as that of the rebels generally, he brought in the common people as full participants.

They were not, perhaps, equals in every sense early on. But they sat alongside the nobles and clerics and took part in the debates and the votes. And what is remarkable is that over the next couple of centuries instead of being squeezed out they continued to gain power and respect, including getting their own separate house within a century with control of its own affairs and primacy on money bills. And people mock the Middle Ages.

The nobles and clerics may generally have been displeased to find knights and burgesses tramping mud into the place. But as the various parliament-like entities throughout Europe succumbed to absolutist monarchs over the next three centuries, the wiser among them must have reflected that the deep roots of the English parliament among the actual people of England were a major reason it, and it alone, survived and flourished, becoming ultimately more powerful than the monarchs as the commons chamber came to dominate the lords.

There is much more to be said about it, including the possibly happy chance that early on the English parliament divided not into three estates as in France, with separate noble and clerical houses, but into two, the mucky-mucks and the ordinary Joes and eventually Janes. And that Montfort’s own motives may have been less than entirely pure, as his conduct was (not least in his vicious anti-Semitism, at once opportunistic and apparently heartfelt). But he deserves respect for what he did.

So does the political culture of the English, and the habits and actions of countless English men and women great and small, through which liberty under law went from success to success despite its challenges. Indeed, though Montfort himself perished horribly later in 1265 at the battle of Evesham where his corpse was nastily dismembered, when his conqueror Edward succeeded his father Henry III and became Edward I, he himself summoned parliaments to which he too invited commoners and to which he reluctantly but decisively surrendered power over taxation.

The history of mankind would be enormously different had representative government not taken hold in England. It is far from established universally and faces challenges even in its Anglosphere heartland. But it is a standing example, invitation and sometimes reproach to all regimes and people everywhere that lack it. And while a great many things contributed to its remarkable history, including the countless again great and small who made Magna Carta a reality and defended it down through the years, Montfort’s innovation of including the common people as full members of Parliament was an important turning point.

Without it things would almost certainly have been different and worse, then and later, there and elsewhere including of course in Canada.

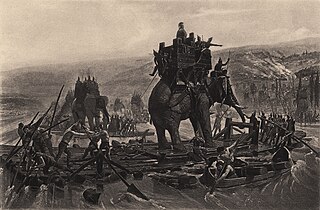

On this date, January 23, Song dynasty troops with crossbows decisively defeated the Southern Han war elephant corps at the battle of Shao in 971. Which might seem a hair-raising and messy irrelevancy. But I record it because I’ve always found it odd that the crossbow was such a mighty weapon with so little impact on military history, and considered elephants an absurd weapon that I can’t figure out what I’d do if the other side showed up with them.

On this date, January 23, Song dynasty troops with crossbows decisively defeated the Southern Han war elephant corps at the battle of Shao in 971. Which might seem a hair-raising and messy irrelevancy. But I record it because I’ve always found it odd that the crossbow was such a mighty weapon with so little impact on military history, and considered elephants an absurd weapon that I can’t figure out what I’d do if the other side showed up with them.