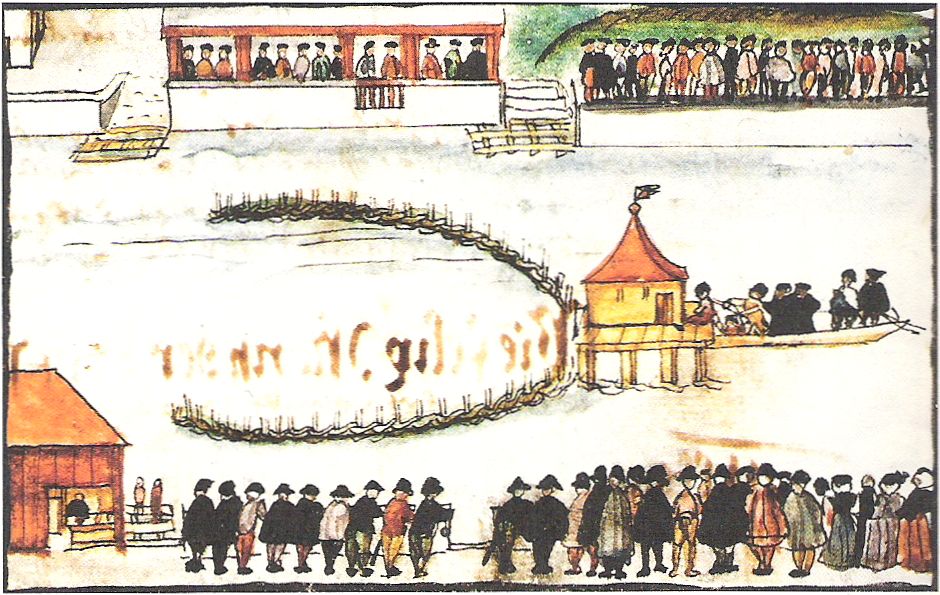

As a result of the "Affair of the Placards," six Protestants were burned at the stake in front of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris on January 21, 1535. And while it’s fashionable to mock those WWJD bracelets as cloyingly sentimental, there are worse questions you could ask yourself. Especially if you’re, you know, a Christian cleric or would-be governmental defender of the faith.

As a result of the "Affair of the Placards," six Protestants were burned at the stake in front of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris on January 21, 1535. And while it’s fashionable to mock those WWJD bracelets as cloyingly sentimental, there are worse questions you could ask yourself. Especially if you’re, you know, a Christian cleric or would-be governmental defender of the faith.

When I say this grisly execution happened "as a result of" the Affair of the Placards, it might be more precise to say it happened afterward and on the ostensible basis of it. The Affair itself was the scandalous posting of a series of aggressive protestant posters in Paris and other French cities denouncing the Catholic mass. They were intended to be offensive, and it worked. But the total number of people killed during their production and display was zero. Not even the King of France.

Here I say "not even" because one of the placards was actually put on his bedroom door in Ambois. It was not merely an affront but a pointed demonstration that had they chosen to they could have gone in and killed him. But they did not, nor did they try to. So he responded with a big public show of affirming his Catholic faith, reversed his earlier policy of trying to protect French Protestants from their more aggressive Catholic countrymen.

Bear in mind that France was dangerously riven by religious sentiment at this point, and a very great distance indeed from any real conception of separation of Church and State. Indeed they still have issues with it, being militantly secular. (I know it has been said that atheism is a religion in the same sense that not collecting stamps is a hobby. But I disagree. Atheism offers equally firm answers to the same full range of metaphysical questions, and to enforce it through the state is not religious neutrality.) So I have to ask two key questions.

First, did either side gain anything by being deliberately obnoxious? I grant the Protestant grievance at being silenced on theological questions and living in perpetual fear of extreme mob violence. (In the wake of the Placards a number of leading Protestants pre-emptively fled France including John Calvin.) But to have posted reasonable comments on the advantages of free discussion of religion would have been a better move, surely, than to put up something highly likely to provoke Catholics into measures that further inflamed feelings in ways that reduced the likelihood of their acting with genuine charity.

As for the Catholics, to respond with extra-legal violence and state murder could not have been better calculated to reinforce their non-co-religionists’ worst suspicions about their motives and the need to arm against them. So everybody lost, and France spiraled into religious wars, intolerance and intellectual stagnation.

Among those who lost most, surely, are the self-proclaimedly Catholic king and the clergy who said there’s probably nothing Jesus would like better, nothing he’d be more likely to do if he were here, than to destroy some fellow human beings as horribly, painfully and messily as possible right at our best church. Oh yeah. I’m sure that’s in the Sermon on the Mount somewhere.