There’s this joke in a book we bought at the Roman Baths in Bath this summer that goes "How do you divide the Roman Empire? With a pair of Caesars." And it’s a good January 17 joke (no, really) because it was on that date in 395 that the heirs of Theodosius I permanently split it into the Eastern Empire under Arcadius and the short-straw crumbling Western bit given to the hapless Honorius.

There’s this joke in a book we bought at the Roman Baths in Bath this summer that goes "How do you divide the Roman Empire? With a pair of Caesars." And it’s a good January 17 joke (no, really) because it was on that date in 395 that the heirs of Theodosius I permanently split it into the Eastern Empire under Arcadius and the short-straw crumbling Western bit given to the hapless Honorius.

I can sort of imagine the meeting where they said look, everything’s falling apart, barbarians are everywhere hacking and slaying, we were world beaters a century ago and now we can’t cope, what should we do? And some smart-aleck says maybe admit defeat, sort of, and hack off that bit of the Roman Empire with whatchamacallit in the middle, you know the place I mean, a pretty famous city, I think it’s, um, Rome, that’s it, Rome. Let’s… ditch Rome. It’s probably on fire anyway. And everybody looks at him funny and then there’s an awkward pause and the chair says "Has anybody got a better idea?" and nobody has so they do it.

It sounds like a counsel of despair. Surely they needed a bold stroke, something to fix the problem, not give in to it. But in fact it was a counsel of wisdom, following a rule that’s easy to state but hard to implement in the press of events: Reinforce success not weakness.

In statecraft, in military matters, and in business it’s far too easy to deal with a problem in the short term by drawing away resources from something that’s working to prop up something that’s not. But the more you do it, the fewer resources you devote to things that are working and the more you devote to those that are not and you spiral downward into defeat, bankruptcy or whatever particular form of ruin you were trying to stave off in the first place.

In fact the result of amputating the rotting western bit was that the Eastern Empire, later Byzantium, lasted more than 1,000 more years though the last four centuries were ignominious and those that preceded it were often squalidly magnificent, with intrigue and decadence behind a shimmering façade. The East badly missed the political and civil culture of the West once it was gone. On the other hand, refusing to face facts would probably have dragged the East down far faster without doing as much for the west as the separation did.

In the short run, the Eastern Empire was able to regroup, husband its resources, and make several determined efforts to recover the West after the Fall of Rome. In the second, the West liquidated its failing arrangements and rebounded dramatically.

I’ve often thought the Fall of Rome was much more of a political and headline event than a truly major historical development. The rule of law remained stronger there than even in Byzantium, let alone elsewhere, Charlemagne did resurrect the Holy Roman Empire by 800 AD and while there is much to criticize about the nature of government even in Western Europe after the 5th century, and many waves of barbarians difficult to stop, it’s hard to think of anywhere you’d rather have lived even then. Especially if you pick the right part, Britain, an important part of the Western Empire for almost four centuries, where humanity later got both Parliamentary self-government and the slow but increasingly effective separation of Church and State in practice that have both eluded almost everyone else to this day.

So take another page from the Romans’ playbook and reinforce success not failure. Mind you, even in the failing enterprises you’d ideally put someone less useless than Honorius in charge.

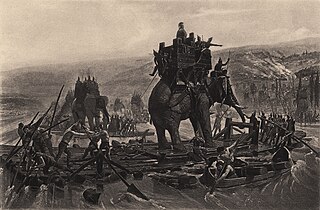

On this date, January 23, Song dynasty troops with crossbows decisively defeated the Southern Han war elephant corps at the battle of Shao in 971. Which might seem a hair-raising and messy irrelevancy. But I record it because I’ve always found it odd that the crossbow was such a mighty weapon with so little impact on military history, and considered elephants an absurd weapon that I can’t figure out what I’d do if the other side showed up with them.

On this date, January 23, Song dynasty troops with crossbows decisively defeated the Southern Han war elephant corps at the battle of Shao in 971. Which might seem a hair-raising and messy irrelevancy. But I record it because I’ve always found it odd that the crossbow was such a mighty weapon with so little impact on military history, and considered elephants an absurd weapon that I can’t figure out what I’d do if the other side showed up with them.