In my latest National Post column I condemn the whole concept of food trends and "cutting-edge flavours" in favour of the retrograde notion of liking things that taste good.

With the 100th anniversary of Canada's great victory at Vimy Ridge fast approaching, I'm delighted to announce that the book version of my documentary The Great War Remembered is now available for purchase.

With the 100th anniversary of Canada's great victory at Vimy Ridge fast approaching, I'm delighted to announce that the book version of my documentary The Great War Remembered is now available for purchase.

The First World War was the defining event of the 20th century, shaping the modern world in ways we still feel very strongly today. Modern technology and logistics created unprecedented slaughter, and partly as a result the long, bitter, bloody conflict undermined faith in Western civilization. But it was a necessary war and the Allies did win it, with pivotal contributions from Canada, which "found itself" in the war and especially at Vimy, not just as a nation, but as a free nation determined to defend liberty under law.

It is appropriate that we remember the costs of the war and lament the loss and the missed opportunities. But we should also remember, and celebrate, the determined spirit that stood up to aggression on behalf of a way of life well worth defending even at this terrible cost.

Order your copy today and take a timely, fresh look at an often misunderstood conflict central to the modern world.

p.s. American and international shoppers should purchase directly through Amazon.

p.p.s. We also have the Kindle version available, here.

In my latest National Post column I argue that the unsettling nature of free enterprise is also the key to its success.

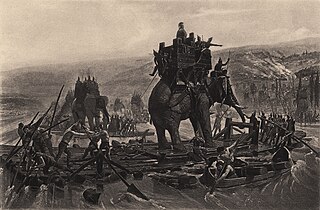

On this date, January 23, Song dynasty troops with crossbows decisively defeated the Southern Han war elephant corps at the battle of Shao in 971. Which might seem a hair-raising and messy irrelevancy. But I record it because I’ve always found it odd that the crossbow was such a mighty weapon with so little impact on military history, and considered elephants an absurd weapon that I can’t figure out what I’d do if the other side showed up with them.

On this date, January 23, Song dynasty troops with crossbows decisively defeated the Southern Han war elephant corps at the battle of Shao in 971. Which might seem a hair-raising and messy irrelevancy. But I record it because I’ve always found it odd that the crossbow was such a mighty weapon with so little impact on military history, and considered elephants an absurd weapon that I can’t figure out what I’d do if the other side showed up with them.

The "mumakil" or "oliphaunts" are a significant problem at the Battle of the Pelennor Fields in the book version of the Lord of the Rings, and a ludicrously overblown one in the movie where they seem to kill about 63,000 of the Rohirrim before Legolas does them all in. But trying to devise a sensible strategy even for the more reasonably elephant-sized ones in the book is a puzzler. So having the Song riddle them with crossbow bolts fired with such incredible energy as to bring down even that big a target works for me.

As it did for them; elephants were then permanently dropped from the main Chinese order of battle. At which point they also started working on gunpowder weapons since once the elephants were gone, there wasn’t a lot the apparently super-cool crossbow could do. Despite at least a millennium and a half of military use of crossbows, this is the only battle I’m aware of where it was decisive.

As for elephants, they were used militarily in parts of Southeast Asia into the 19th century. Elsewhere it turned out they reacted even worse to cannonballs than crossbow bolts.

In my latest National Post column, I challenge climate alarmists to explain the past before they predict the future, as the scientific method requires.

English weather is proverbially lousy partly because it’s so wet all the time. But January 16 of 1362 was especially bad, the onset of the Grote Mandrenke which if your low Saxon is in good working order will alarm you because it means the "Great Drowning of Men".

English weather is proverbially lousy partly because it’s so wet all the time. But January 16 of 1362 was especially bad, the onset of the Grote Mandrenke which if your low Saxon is in good working order will alarm you because it means the "Great Drowning of Men".

Also known as the "Second St. Marcellus Flood" because it peaked on his feast day, January 17, the Grote Mandrenke took at least 25,000 lives in the British Isles and northern Europe from Denmark to the Netherlands. A previous "First St. Marcellus flood" had hit in 1219, drowning some 36,000 people in northern Europe, which surely indicates that extreme weather did not begin when Al Gore hit middle-age.

In fact the Grote Mandrenke was the result of a massive southwesterly Atlantic gale that sent a storm side surging far inland, sweeping away islands, cutting off parts of the mainland and wiping entire towns off the map to the point that some cannot now be located even through archeology. And it was, as the "Second St. Marcellus flood" business indicates, far from unusual in that period.

Wikipedia notes blandly that "This storm tide, along with others of like size in the 13th century and 14th century, played a part in the formation of the Zuiderzee, and was characteristic of the unsettled and changeable weather in northern Europe at the beginning of the Little Ice Age." But hang on. Doesn’t that sound exactly like "climate change"? But hardly "man-made" or, if you like long words, "anthropogenic."

OK then. If drastic, menacing climate change has been clearly happening since long before humans invented factory mass production, and has been known to have been happening, it tells you what?

The politically correct answer is nothing. Everybody contemplating any issue other than the current panic knows climate has always varied, often suddenly and with dramatic consequences, and says it openly. Glaciers suddenly advance and suddenly retreat. The Earth warms and cools repeatedly. But never mind. Pay no attention. The science is settled. It’s all our fault.

Except the science is no more settled than the climate itself. The famous "Little Ice Age" itself, which brought the Middle Ages to something of a screeching halt and lasted into Victorian times, was not caused by humans. But nor logically then was its end, which set off the warming trend that persisted through most of the 20th century. Indeed most of that warming awkwardly preceded the large increase in atmospheric CO2 to which it is attributed by those who do not believe that causes must precede effects for science, or life, to make any sense.

Blaming humans for unstable weather is about as rational as blaming St. Marcellus. Which people in the Middle Ages were too sensible to do, I might pointedly add.

In my latest National Post column I say that neither Jane Fonda nor the rest of us can reach low-carbon nirvana just by really nicely really wanting it.

Merely saying the name of the 7th planet in our solar system risks provoking adolescent snickers. Especially when you add a moon or two of… Uranus. There. Now that we’ve disposed of that issue I’d like to raise a glass, carefully ground for optimum magnification, to William Herschel.

Merely saying the name of the 7th planet in our solar system risks provoking adolescent snickers. Especially when you add a moon or two of… Uranus. There. Now that we’ve disposed of that issue I’d like to raise a glass, carefully ground for optimum magnification, to William Herschel.

He it was who first discovered that planet, the third-largest and fourth-heaviest in the Sol system, in 1781. Or rather, discovered that it was in fact a planet and not a comet or a star. Despite which he wanted to name it the "Georgian star" or "Georgian planet" which is only funny in a sad way as it was an obsequious attempt to curry favour with King George III. I guess it worked, in that the German-born Herschel was appointed "The King’s Astronomer" by the German-descended king a year later. But the French were so unwilling to utter the name of the British king (I don’t see why; it’s not as though they were stuck with him) that they called it "Herschel" until the name Uranus was adopted after a long and on the whole civil debate of exactly the sort we don’t now have on the Internet. And by many people in whose language it wasn’t a double entendre, I might add.

As I might add that it was also Herschel who, on January 11 of 1787 discovered two moons of Uranus subsequently named Titan and Oberon by his son John. And it strikes me as worthy of commendation because it is so useless. To be sure, Herschel didn’t know it at the time. He was convinced the moon was inhabited, and that its settlements resembled the English countryside. (He was also certain Mars was inhabited, and the inside of the sun.)

If Uranus’ moons had been inhabited, perhaps we would have learned great scientific or cultural secrets from them. Like that the sun is extremely hot, say. Or that disinterested curiosity is a good thing. If they were even reachable, they might furnish thrill-seeking tourists with something special to do before you die like witness a methane waterfall. Right before you die, I mean.

Still, I feel that Hershel more or less stared into space because it was there, and found weird celestial bodies because they were. (While not composing one of his 24 symphonies along with many other musical works, in case you want to feel inadequate.) And he went right on finding cool things in space, like that the ice caps on Mars change with the seasons, that our solar system is moving through space and so forth. And to do something periodically without a covetous eye on the outcome is a good thing. As for his securing career advancement through it, well, it just shows a society exhibiting disinterested curiosity. And there are many worse qualities.